Will digital art spice up food ?

Article author :

From theatre to dance, by way of music and the visual arts, the digital technologies are now embedded within the ensemble of the contemporary creative disciplines. Every discipline? No! For one domain is time and again putting up stern resistance to the digital technologies (for the moment, at least). In fact, gastronomy – formally called culinary art, in the vernacular known as food – has to date experimented but little with the creative potential of the digital world. What are the explanations for this? What experiments have already been attempted? What ideas could we come up with to encourage the emergence of connections between digital arts & food?

Art & food, an aestheticization of the world

Let us assume a premise to ground this investigation: art & food are subject to the same influences and are caught up in the same historical movement. In other words, each is in a conversation with the other. This is essentially the diagnosis offered by David Morin Ulmann, a teacher at the Food Design Lab of the Nantes Design School. ‘There is a porosity between food and art which from an anthropological perspective can be analysed as a form of domestication of the world. Human beings look to exalt the environment they transform. One might speak of a productive aestheticization.’ If pre-modern art movements were reserved for the sacred and the religious (in painting, music and architecture, for example), we can see the same thing occurring with food. ‘A few centuries ago drinking wine was reserved for the deities. God is omnipresent in art and food. Over time, we have as it were “secularised” art and food’. Both form a single reflection of our society. ‘In every century, gastronomy – foodstuffs, rituals and routines – can be compared to an art movement. Let us take the use of the word “food”, for example. It is an English word which the whole world has appropriated. It is the preeminent symbol of a pop culture in which no matter what the time is, the day of the week it is, we all end up eating the same meals.’ If we adopt this reasoning, then contemporary art would discover its counterpart in contemporary food. David Morin Ulmann takes this further: ‘Molecular cooking conceptualises the idea of the taste of foodstuffs. We are very close to conceptual art and a performative aspect. Another example, miniature food embodies a kind of idealisation of food. It is a process of spiritualising food. Likewise for healthy food or vegetarianism.’ We can also see an idealisation/spiritualisation in the work of a good number of current artists in their evoking of Nature or ecology.

Omnipresent technologies…

If food and art are the reflection of our society, how do they take material form in 2023? Since the years 2000, art has become highly digitalised by embedding, to varying degrees, digital technologies at the heart of artistic disciplines. That has brought about a hybridisation in creation. The reappropriation of the means of production – through the philosophy of free software, of fablabs equipped with 3D printers or laser cutting machines – is a pathway which digital artists stand by. In addition, how could we not bring up the emergence of generative AIs, with the upheavals it is causing already starting to have an impact, in the audiovisual sector, for example? Finally, a last illustration if a further one is required, the advent and the structuring of the XR market (a generic term to talk about virtual reality, augmented reality, etc.) now offering immersive experiences in the cultural domain, especially in live performances. There can no longer be any doubting the evidence: the digital is an integral part of contemporary art!

Let’s turn to the food aspect now. The digitalisation of tools is undoubtedly making its very visible mark in the food industry. There are, first of all, announcement effects, too often within the realms of fantasy, such as when McDonald’s announced in 2022 the launch of shops in virtual reality. Then there are self-evident facts: the recent appearance of FoodTech is indicative of a genuine food digitalisation. This FoodTech designates the ensemble of entrepreneurs and start-ups in the food sector (from production to end consumers) which is innovating in terms of products, distribution, the market and the economic model. According to the AgFunder report, in 2022 FoodTech represented a global market of 250 billion Euros, taking in over 4,000 start-ups across the world (with around 1,500 in Europe, including a hundred or so in Belgium). These actors meet up just about everywhere across the planet at events on an international scale, such as the FoodTech Summit in Mexico, or on a local level, such as the FoodTech festival in Nantes. Nowadays, the FoodTech market seems to be an El Dorado well structured around different sectors: AGTech (the development of future agricultural farms), Foodservice (improvements in services, for professionals and private individuals), coaching (guiding consumers by means of applications), Foodscience (nutrition and food innovation), etc. Quite apart from the numerous specialised consultancy firms and multifunction Labs – such as the Digital Food Lab in Paris or the Smart Gastronomy Lab located at the Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech faculty in Belgium – which offer incubator services for start-ups or advice to business companies looking to accelerate their digitalisation.

… but not completely in food

On that precise subject, Dorothée Goffin, the director of the Smart Gastronomy Lab, explains in an interview published on kingkong that ‘agro-food and nutrition are the last major thematics which still haven’t incorporated digital technologies. Yet it is important to explore them for creative solutions to obtain better monitoring of food processing procedures or the behaviours of consumers. From our perspective, food technology is not about developing a hyperconnected kitchen with robots putting together meals in our place […]’ Dorothée Goffin tacitly highlights an important point: it has to be said that the robotisation of household appliances and the emergence of connected objects – refrigerator, robot pressure cooker or connected tray – serving to define the profile of the consumer (a similar experiment designed by the Smart Gastronomy Lab was tested in 2022 at the KIKK festival) – are on their way to becoming familiar in everyday use. Ironically, the abundance of the supply of household appliances offers a certain modernity to the ‘Lament of Progress’, sung by Boris Vian in 1956. Be that as it may, the technologies such as they are deployed in the remainder of current and previously mentioned contemporary creation are still far from having featured in the most creative gaps of the food domain (culinary design, sensorial experiences, kinaesthetic cross-fertilisation, etc.).

Reciprocal inspirations

The balance sheet is thus the following: food and digital art have not (yet) succeeded in creating bridges. For all that, this lack of transversality does not mean that digital artists have no interest in food. Far from it! This engagement occasionally manifests itself through a reinterpretation of an artistic genre. In this way, Table Props, by the Belgian artist Alex Verhaest, is a series of still lifes in video – a broken plate, an overturned glass, sprinklings of breadcrumbs – combining technology and classical aesthetics. This staging of food reveals itself as finely wrought allegories of our psychological states of mind and brings into focus the cultural and social aspect of gastronomy. Another example can be found in Albertine Meunier’s series HyperChips, where every image has been created on the basis of the same prompt, ‘Albertine Meunier is eating sausages and chips’. Next, AIs of the Dalle-E and Mid Journey type generate hundreds of visuals revisiting the art of the self-portrait and staging foodstuffs which are symbols of a globalised culture. And how could we not mention mEat me, the incredible performance by Theresa Schubert which questions our relationships with meat and our own bodies. In this work, the artist manufactures a serum extracted from her own blood. It is used to reproduce her muscle cells and turn them into edible meat. Theresa Schubert shifts the normative boundaries and dissolves the consumerist hierarchies between human beings and animals by suggesting a new perspective on food provision. Finally, it may well be the whimsical foodscapes by Carl Warner which best summarise, not without humour, the particular attachment artists cultivate for food imagery.

The cultural and creative industries are also testifying to an appetite for this food culture. The high-spirited liveliness of reality TV programmes or cinema productions is an example of this proximity (from La Grande Bouffe to Délices de Tokyo, without forgetting Ratatouille). The programme Blow-up, broadcast on ARTE, demonstrates how loquacious the 7th art is on the subject, drawing inspiration as it does from this universe. The gaming industry is not letting itself be outdone either. The fruits swallowed by PACMAN in the 1980s, the symbol of a gaming iconography, are prophetic of dozens of video games published in the four following decades (with smash hits such as Cooking Mama, Chef Life – A Restaurant Simulator or The Sims 4: Dine Out). The interest which the independent studios are taking is just as fascinating to observe, with audacious products having appeared in recent years, such as Venba (Visai Games), where the goal is to cook dishes which have been forgotten following an Indian mother migrating to Canada in the 1980s. Or the game Hot Pot for One (Rachel Li), in which is incarnated a character who finds themselves alone in a foreign land during the Christmas celebrations. To cope with this emotional situation, the gamer prepares a hot pot, a traditional Chinese dish. Two original games which underline the intercultural dimension, the experiential aspect of food.

Trying out hybridisations

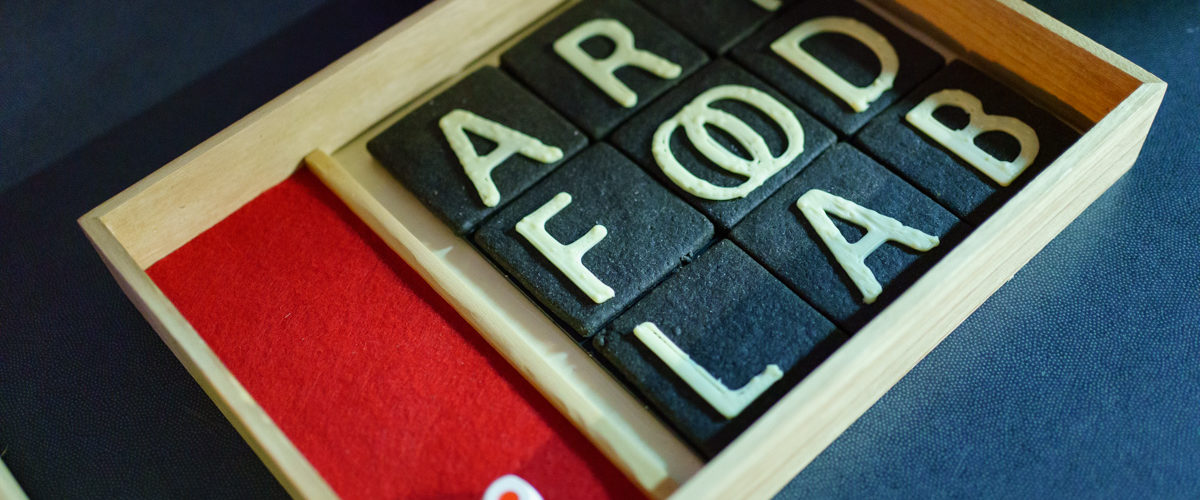

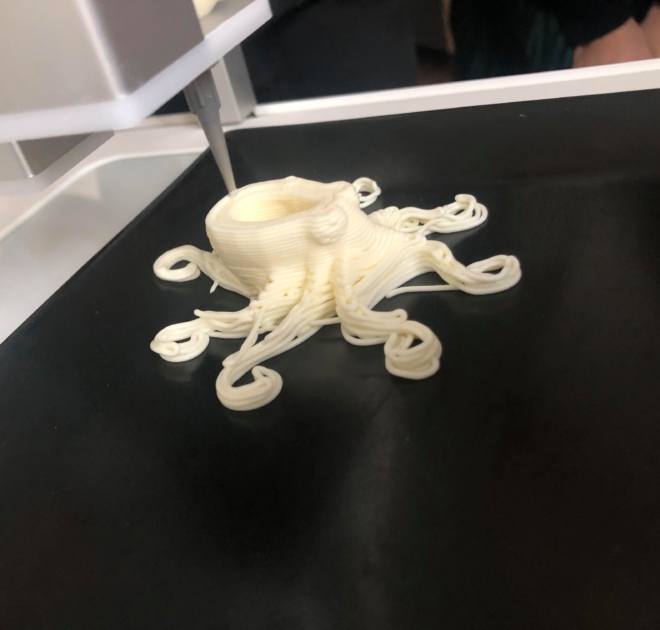

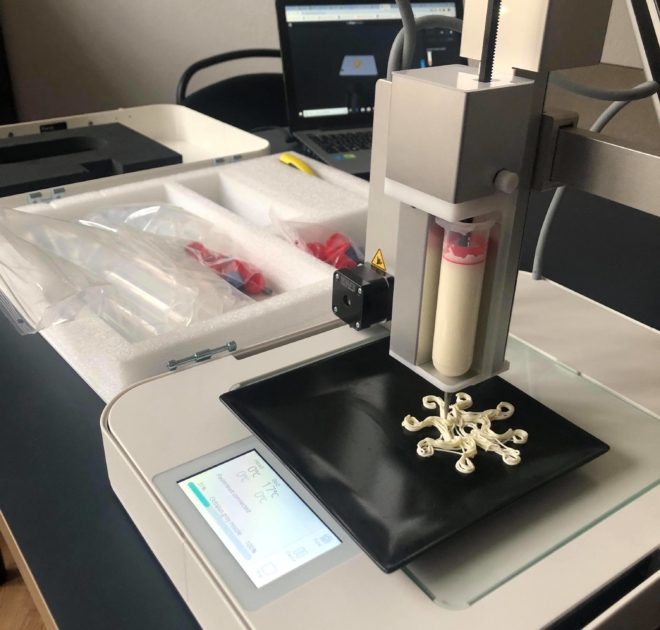

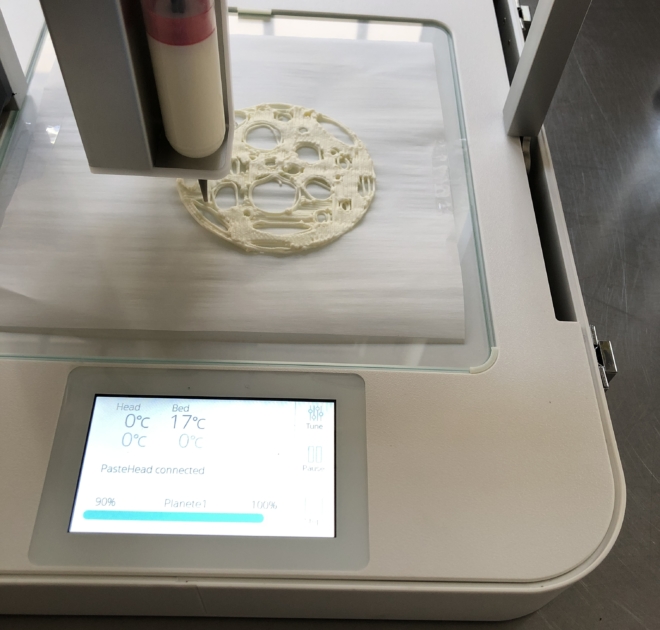

Hybridisation initiatives are nevertheless rarer. In a somewhat isolated, one-of-a-kind manner, certain artists such as the Cuisine Sauvage duo imagine low-tech installations in a completely unabashed style. Take for example the churro manufacturing extruder jointly created with the artist François Dufeil, assembled using fire extinguishers earmarked for the scrapheap. There are all the same several associations establishing genuine cross-fertilisation projects between the digital arts and food. One such collective initiative is the Ososphère in Strasbourg, which pilots the ArtFoodLab project. ‘The ArtFoodLab was launched in 2019, with the idea of offering an experimental lab intended to be long-lasting. The objective is to create interdisciplinary skills around gastronomy. A culinary designer and several chefs are thus brought together by this laboratory and are taking part in several events. It has become apparent that if we wish to demonstrate creativity, we have to understand the whole of the gastronomy chain, all the stages of production… That enables us to come up with very different experiments concerning the form, the texture, the taste,’ explains Thierry Danet, the director of the Ososphère. Experiments which are embedded in a local fabric with its own cultural specificities. ‘In 2022, the ArtFoodLab organised a brunch involving the residents of priority neighbourhoods of the city of Strasbourg. The central theme was a kugelhopf cake mould which, in its way, tells the story of the town and its history, which are a lot more hybrid than the clichés of folklore would have you believe. Over a period of several weeks, we collected family recipes from our neighbours. They were then reinterpreted by the chef and the culinary designer through 17 recipes. 3D prints were included in the preparation of the kugelhopf cakes. It was an interesting work on the shape because we included this shape in individual and collective stories to be shared. We attempted a sensorial approach by mixing music and food. A kugelhopf cake enabled samples to be triggered and so a sound score could be composed. Stéphane Kozik was the one who developed this performance, which he subsequently reworked by involving the guests in a composition which was simultaneously musical and danceable, on the basis of sounds picked up during the live broadcasting of the preparation of an apple pie and a smoothie.’ Stéphane Kozik is for that matter well versed in the genre: in Digital Breakfast, together with his partner for the occasion Arnaud Eeckhout, he reimagines the world of the breakfast. They create a surrealist sound and visual world, composed of kitchen equipment and foodstuffs transformed into digital musical instruments, thus producing a narrative research project.

Immersive gastronomical experiences

Lighting devices are also integrated within other narrative research projects. In certain cases, mapping becomes a tool offering invitations to a multi-sensorial experience. In 2022, the Geneva Mapping festival placed several immersive meals on its programme. La Cène offered a multimedia-culinary experience reinterpreting Dante’s Divine Comedy. The guests are guided by a narration conveying the descent into Hell, the passage through Purgatory and the spheres of Heaven. Videos and projections bring to life the plates and the scenographic space. Other associations are also becoming aware of the potential of immersive apparatuses in the food domain.

The emergence of XR (virtual reality, augmented reality, etc.) has encouraged the imagining of several enthralling experiences. The Artechouse, a gallery established in the United States and entirely dedicated to mapping, has involved AR technology in its bar’s cocktail menu. Each drink scanned activates its own animation and puts on a show for a clientele which has turned up precisely looking for a unique experience. Another striking initiative: Aerobanquets RMX, presented in 2022 at the Miami Art Week, is a mixed-reality experience created by the artist Mattia Casalegno and the chef Chintan Pandya. Inspired by F.T. Marinetti’s ‘The Futurist Cookbook,’ a collection of surrealist and utopian recipes from the 1930s is offered. In this immersive gastronomic experience, the textures and flavours are reproduced in virtual scenes, but designed and savoured in real life. ‘The senses are more open. You are more attentive and aware of what you are eating,’ explains Mattia Casalengo to Artnet News. ‘Virtual reality is a way of extending the senses and focus more on taste and texture.’ We are just a small step from there to talking about augmented food…

What will tomorrow bring?

Let us nevertheless keep our feet on the ground. As things currently stand, collaborations between digital artists and food professionals are still a rare occurrence. How can the emergence of new connections be fostered? First of all, by removing several existing obstacles. Whilst many might believe that the digital technologies are incompatible with food health and hygiene standards, that does not appear to be a real problem. ‘There is nothing which cannot be resolved. Certainly, there are stringent regulations, but it’s just a question of good will and professionalism. In the world of art, there are always important and restrictive regulations concerning safety and accessibility for instance. And yet we always manage to keep moving forward,’ explains Thierry Danet.

The main challenge lies in the ability to bring together artists and operators in the food domain. In this respect, third spaces, fablabs, cultural institutions and other Labs are anchor points within regions and essential links to powering a creative dynamic. Thierry Danet makes the same observation. ‘It requires digital arts associations to act as driving forces. When our reflections have advanced several steps further, we will mobilise renowned chefs de cuisine in the Grand Est region. We will try to shake up their practices by bringing them together with artists. There is really something to be done here. The risk would be to get things confused and reduce the artistic dimension simply to that of food presentation, whereas gastronomy has become a privileged site for sharing arts issues at a personal and collective level. But by including all of the actors in an area, we can bring about new creative reflections.’ David Morin Ulmann agrees wholeheartedly that there is this need for transversality and knowledge sharing. ‘I notice that in certain schools, the media and food options are separate. There is a corporate spirit which maintains an absence of transversality and a lack of interest in digital technologies. Students are asked to carry out UX experiments without necessarily mastering the digital tools and the uses they can be put to.’ Challenges which are far from being insurmountable. But let’s make no bones about it: there is a lot of work to be done!

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

Three days at the Wallifornia MusicTech Summit, in the “Cité Ardente”

When the video game (over)does nostalgia

Amélie Lachapelle: ‘the digital transition will have to be green or it will not take place’