When the video game (over)does nostalgia

Article author :

Remake, reboot, revival of licences we thought had vanished. For several years now, the video game industry has been recycling hand over fist the titles that made it an outstanding success story several decades ago. The reason for this trend: the videogaming industry’s use of nostalgia. A powerful marketing argument, but one which has its limits.

Tomb Raider was released 28 years ago, Final Fantasy 7 27 years ago, Spyro the Dragon 26 years ago. Does that make you feel old? In fact, the video game recently celebrated its fiftieth birthday. Quite the milestone for an industry which has never ceased developing, evolving from an occasional slightly guilty pleasure for nerds into a hugely popular social phenomenon (both in the playgrounds and at the workplace) and one more profitable than the cinema.

This longevity ensures that, today, the medium can draw on an extremely wide pool of players. There are of course the very youngest, who are discovering their first games, controller in hand, and who, for the publishers and the studios, remain a favourite target market because they are relatively easy to keep happy.

On top of that, there is another type of audience which is just as attractive, and maybe even more so for the industry. These are the experienced players: those who have racked up countless hours over time. Those who grew up with video games.

A ‘well-to-do’ audience hungry for nostalgia

Today they are aged between 25 and 60. They are adults and they work. They therefore have more means to buy themselves games. But it is not an easy audience because, having had the opportunity to try their hands at numerous different titles, they are more critical and harder to convince.

In this context, the industry has for a number of years employed the same tactic: attempting to innovate, offering games with new concepts, with ever more attractive graphics, worlds which are ever bigger, storylines which are ever more layered. The whole package developed by ever larger teams, sometimes made up of hundreds of employees.

But, as a consequence of this, the commercial flops have become more painful, financially speaking. At the same time, this audience greedily targeted by the industry has become more and more difficult, with an ever-expanding range of games from which to choose. A solution had to be found, and the publishers came up with a neat idea: playing the nostalgia card.

By reviving the licences and the titles idolised by these players years (even decades) previously, they have managed to play on their heartstrings, evoke lived moments, good childhood or teen memories intrinsically linked to happy periods in their lives.

Enough to lower the guard of these reputedly ‘difficult’ players, with the means to spend lavishly to get one more taste of Proust’s madeleine.

Reboots and remakes galore

Another advantage of this strategy is: it costs less. There is no need to start from scratch. As the basic material already exists, all you need to do is adapt it. For several years now, the video game industry has largely relied on three techniques to do this.

The first is the remake. The recipe is a simple one. Take a video game which left a mark on its generation several years ago. Reuse pretty much the exact same storyline, as well as its gameplay (in other words its rules and the way it is played), and adapt the graphics and the menus with today’s technologies.

A major advantage of this technique is that the risk involved is low, because material which has been tried and tested is used and retained as-is, in addition to ultra-low production costs owing to the limited resources and personnel required to successfully undertake this work. Some striking examples from recent years include The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, Spyro the Dragon, Crash Bandicoot N. Sane Trilogy, Dead Space and Resident Evil (in the latter case, Capcom, the publisher and owner of the franchise, has produced a remake of the full set of Resident Evil games published).

Another slightly more expensive technique is the reboot. The process is somewhat different here. The goal is to keep the aspects that were a licence’s strong points and give the licence a completely new direction in the form of a new title. It is therefore not a sequel because it instead involves ‘rebooting’ the licence. Some standout examples of this method are God of War, Tomb Raider, Doom, and Ratchet & Clank.

Finally, there are the sequels which, unlike the reboots, establish a direct continuity with the preceding opus. The most successful example of recent years, one we have already talked about at length, is Baldur’s Gate 3, released 20 years after its predecessor.

The limits of nostalgia

However, the limits of this relentless fixation on nostalgia are starting to show. On the one hand because the stratagem, having become more and more blatant, has made players more distrustful of works which, for some, were no more than pale imitations of the original game. On the other, because the feeling of nostalgia itself tends to skew our judgements. We instinctively idealise memories of the past, by mingling them with a particular context. This renders the constituent parts more beautiful and more magical than they actually were.

Accordingly, when we get reacquainted with a video game from the past, we may be disappointed because in playing it again the original feelings elude us. This disappointment is one which many players have felt with the mass of remakes, reboots and sequels placed on the market. And they are now far more wary of succumbing to the sirens of nostalgia.

Finally, there is the inability of developers to reproduce the originality and the quality of something that was a success in the past. Without the original context in which the games were successful, it is much harder to replicate those successes.

A recent example is provided by the Belgian studio Appeal and its reboot of the legendary licence named Outcast. The game, released in 1999, made a big impression, winning over not only the specialist trade press but also the players of the time. And it owed this success primarily to the system of graphics rendering, employing voxel technology, an innovative process at the time which offered a very detailed result, even on less powerful computers. Combined with an accomplished storyline and game design, the game has made its mark on posterity as one of the cornerstones of the Belgian videogame industry.

Yet, at the start of this year, Appeal tried to rekindle the spark with ‘Outcast – The New Beginning’. The concept: to revive the mythology of the original game, the same hero and the same universe, but to offer players an adventure in open world format, with artistic direction and graphics worthy of a major production and completely rethought gameplay.

Unfortunately, the game has failed to convince. In the opinion of the trade press, it is its lack of originality, its particularly flat scenario, its uninspired open world and its shortcomings in terms of pace which are to blame. But the main reason for its failure is its inability to emulate the prowess of its older sibling, which stood out from its competitors thanks to the originality of its graphics engine. And without that, Outcast is merely an average game, very far removed from the idealised memories of people who, like us, adored it in 1999.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

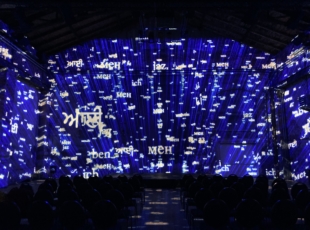

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

NUMIX LAB 2024: creating bonds and building the future of digital creativity