Working in the era of artificial intelligence

Article author :

Historically, each technological revolution has simultaneously destroyed and created employment. Yet, since the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, the fear of the automation of work and human beings being replaced by machines has heightened. Once we have got beyond addressing the issue from the single viewpoint of threat, would it be possible to consider AIs as our new coworkers? A number of thinkers and workers seem to be adopting this position.

You hear it talked about at every opportunity. On kingkong as well. The AIs are everywhere. And if there is one domain above all others which is continually scrutinising the impact of the huge influx of these intelligent algorithms on our lives, it is well and truly the job market. When the kingkong editorial team decided to address the issue of AI in the workplace within the scope of a case study, we quickly realised that the subject is a polarising one. Antis, on the one hand, pros on the other: pick a side. And then there are articles with eye-catching headlines, such as: ‘An AI stole his job’. In it we read the story of Léo, a self-employed translator disillusioned by generative artificial intelligence.

Statistics on the subject are constantly pouring in and they all try to predict which sectors are to be avoided if you are looking to build a career over the long term without being replaced by an AI. Since the emergence of these smart tools, various categories of job are thought to be more vulnerable than others. Banking, insurance and accountancy employees, office and executive secretaries, checkout staff and self-service employees, warehouse workers, etc. In August 2018, the Institut Sapiens thinktank was already listing these various professions in a publication entitled The impact of the digital revolution on employment. Threatened by AI and the automation of work, these professions could simply cease to exist over the course of the 21st century, the thinktank points out.

Last August, in its report, Generative AI and jobs: A global analysis of potential effects on job quantity and quality, the International Labour Organization (ILO), for which the United Nations is an umbrella, showed that the effects of these autonomous intelligence systems vary considerably depending on the profession, on the gender – women are twice as likely than men to see their work affected by AI owing to the over-representation of women in office work, in particular in countries with high or intermediate incomes – or on the geographical zone. 5.5% of the total employment in countries with high incomes is potentially exposed to the effects of the automation of generative AI, notably due to the greater number of office jobs, against merely 0.4% of the employment in low income countries.

Nevertheless, the ILO also emphasises in its analysis that AI is more likely to create jobs than to destroy them. A potential which is often downplayed in the face of the threat. AI ‘will enable certain activities to be assisted rather than replaced […] Thereby, the main consequence of this new technology will probably not be expressed by the destruction of jobs, but rather by potential changes in the quality of jobs, in particular as regards work intensity and autonomy,’ the study reveals. With a potential number of jobs created by AI which is practically the same in every country. The ILO suggests that with specifically adapted policies which support ‘orderly, fair and consultative transitions’, this new wave of technological transformation could in particular offer numerous advantages for developing countries. News which chimes with the figures reported by the Belgian company RH Acerta: 14% of companies are expecting to have to fire a proportion of their staff, but over eight out of ten Belgian employers (82%) consider that even with advanced Ais, they will always need just as many workers.

The stories behind the figures

What interested us the most at kingkong when we set about developing this case file was getting the opportunity to have discussions with those most affected. We therefore launched an appeal for testimonies: ‘Have you fully integrated AIs into your daily life at work, as new coworkers? Have you been trained in how they operate and understand their limits, in such a way that enables you not to demonise them? Alternatively, do the AIs at work worry you and do you feel out of your depth? Tell us about it!’ Reactions from a surprising diversity of professions made their way to us: consultant, graphic designer, mediator at a museum, artist, teacher in secondary and higher education, etc. The majority of these accounts report a rather recreational use of AIs, or tell of their being used to draft content in order to save a little time on a daily basis. But others have a closer relationship with these smart technologies.

AI enables me to be inspired and sketch my future artistic choices.

Nawal, an employee at a European politics thinktank and an audiovisual artist

An employee at a thinktank active in the domain of European politics, Nawal* explains that he uses the now well-known ChatGPT as an assistant: ‘When I have to write a description of events or a report, I provide it with the main ideas and I ask it to develop them. On this basis, I select the expressions I like. It saves me a hell of a lot of time.’ But when he leaves his office and slips on his audiovisual artist’s hat, the twenty-something confides that he uses other AI technologies. ‘I regularly use DALL·E for still images. I find it extremely valuable at several stages of my art projects. In the research and the conceptualisation, I simply try out a few prompts and see what it suggests. It is a very freeform process which enables me to be inspired and sketch my future artistic choices. At a more advanced stage, when an idea is taking a more definitive shape, AI can also aid me if, for one reason or another, I cannot manage to put my thoughts into images.’ Nawal also uses Kaiber, a video generator. ‘You can easily create a video from start to finish with a prompt which explains, for example, the camera movements you want. But personally, I use it instead by providing it with a video as a work basis. I do a lot of stop motion (Editor’s note: an animation technique which captures a series of images to bring to life inanimate objects when they are projected in sequence). I, first of all, film a sequence of several seconds which I use as a baseline to be altered on Kaiber.’

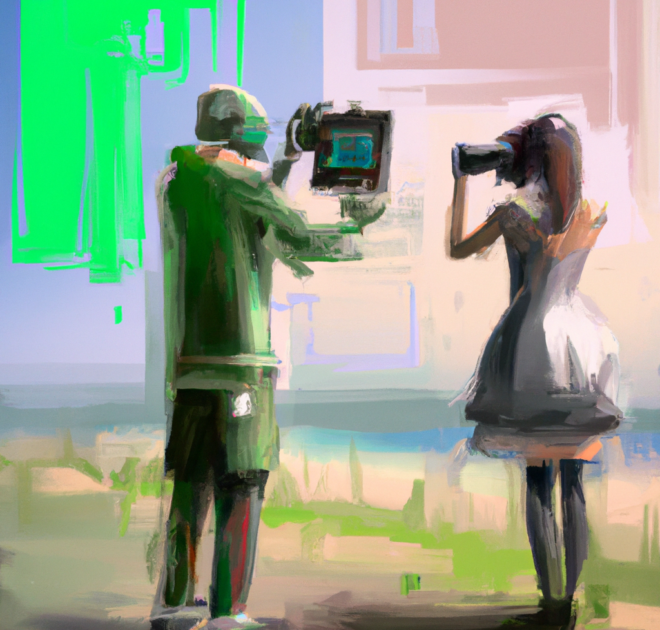

Nawal is not the only artist who contacted us. Valentine Nulens and her partner Timoté Meessen are both photographers who regularly use AI to retouch photos. ‘I have been using AI for a long time without even being aware of it,’ explains Valentine. ‘AI technologies are integrated into the most commonly used photo editing programmes such as Lightroom and Photoshop. I found out about it at a ChatGPT training course I took within the scope of my work in the events business. But over the past few months, AIs have been proliferating in these same programmes. They are even promoted in them. Correcting a backdrop manually using the stamp tool previously took me tens of minutes. Today, in 20 seconds, the programme reproduces a backdrop with stunning precision. On a photo taken at night which displays a lot of grain, the noise reduction feature systematised by an AI allows me to retrieve an image as if it was taken in broad daylight!’ she continues, still marvelling over the tool.

I do not think that AI will one day replace my profession because even though amateur and professional photographers can become better technically, AI will never take the place of an artistic vision.

Valentine Nulens, photographer

More recently, the photographer couple has also tested new software based on an AI: Imagen. A photo-editing assistant which several of their photographer acquaintances are already using. ‘After having loaded several thousands of already retouched photographs into the software, Imagen learns to retouch in our specific style. I wouldn’t blindly trust this programme, but I tested it and feel that in general it respects my style very well. I think it remains ethical to use this type of technology when you are working in large quantities and that allows us to send our photo-reportages more quickly to our clients.’ But all the same you need to be on the lookout for possible abuses carried out by certain people who may train the AI to use it in the style of another photographer. Nevertheless, Valentine states that he is not intending to integrate Imagen into his work because retouching remains a pleasure at the heart of his profession. ‘I do not think that AI will one day replace my profession because even though amateur and professional photographers can become better technically, AI will never take the place of an artistic vision.’

A journalist for Moustique Magazine, Nicolas Sohy is also persuaded that with specifically designed usage, AI could enable any person to become better at their profession. When we meet him in the editing suite of the weekly magazine, in the offices of the IPM group in Brussels, the thirty-something confides that nevertheless AI is not drawing in the crowds in his sector. ‘I started using AI a little over a year ago. ChatGPT first of all, like everybody, then other tools such as Perplexity. A counterpart to ChatGPT, less puritan, I would say. And then, more recently, Cockatoo. A very effective transcription tool based on AI which would be useful to a large number of us, because I know no journalist who likes transcribing their interviews by hand. I could see the phenomenon gaining momentum and very quickly I was led to write on the subject for Moustique, and to meet experts. All of them pointed out to me that we are still far from fully understanding the potential of AI.’

AI makes me more effective as a journalist because when I get to an interview, I feel a lot more prepared than previously in front of my interviewees, I am more on top of my subjects.

Nicolas Sohy, journalist

Having continued to develop his knowledge in terms of smart technologies, Nicolas integrated several AIs into his daily life in order to refine his journalistic work. Primarily during the research phase of the subjects he is looking into. ‘When I get started on a new subject, I, first of all, carry out an interview with the fee-paying version of ChatGPT, which is connected to the internet and is a good deal more powerful than ChatGPT-3.5 (the free-of-charge version, Editor’s note). With practice, I discovered with which prompts I could obtain the most relevant results. I put them into context with the subject I am working on, I specify to it very precisely the types of source I wish it to use, I give it as many items as possible. Afterwards, it’s up to me to check the information it provides me with. But I wouldn’t say that it saves me hours of work in comparison with my previous practices.’ It is for that reason that Nicolas Sohy remains convinced that AI will never replace journalists but may become an authentic work colleague. ‘AI makes me more effective as a journalist because when I get to an interview, I feel a lot more prepared than previously in front of my interviewees, I am more on top of my subjects.’

Nevertheless, when he begins to talk about AI with his colleagues or on LinkedIn, where he regularly posts on the interactions between AI and the journalist profession, a certain reticence is felt. ‘Up until now, no structural strategy regarding AI has been implemented within my editorial team. And I don’t think I am getting too ahead of myself when I say that, in Belgium, the situation is the same in other press groups. However, there are heaps of ways of integrating AI structurally so that it may assist us in our trade. Whether it be to analyse social phenomena, to help us in the editing of our articles, finding effective headlines for search engines, process news dispatches, but also to challenge our sociocultural biases and help us become more objective. I am not the only one who thinks that if we do not look into this issue today and that if we do not train journalists in AI better, as much in terms of the use made of it as in terms of its potential abuses, the profession could quickly find itself overtaken by technology. And that is where the danger lies.’

AI will not mean an increase in productivity through the automation of tasks, but instead an increase in quality by means of better interaction between humans and machines.

Yann Ferguson, a Doctor in sociology and a specialist on the impact of AI on the job market

Automation, the replacement of work, an increase in productivity, etc. The AI technology boom has made workers in every sector fearful. And according to Yann Ferguson, a Doctor in sociology and a specialist on the impact of AI on the job market, what scares the whole of the social body in particular is the word ‘intelligence’. ‘People consider AI a rival. If we go back to the early days of machine intelligence, before it was even called ‘AI’, the Turing test in 1950 already consisted of saying that if the machine can pass itself off as a human being, we must therefore consider it intelligent. From the outset the mathematician Alan Turing placed this hot topic on the table: in short, if a machine appears intelligent, it is thus the equivalent of human intelligence. This form of non-living intelligence, quite active in the mathematical domains, has capabilities and a power which are stronger than us, without a shadow of a doubt. We have always feared the discovery of an intelligence superior to us which, if science fiction is to be believed, could develop free will and begin to make decisions in our place. But what is also feeding the fear in the face of the vast influx of AI in the workplace is that these enormous data systems and the ways in which AI arrives at a result remain opaque. In a company, the injunction to use these intelligent machines can be paradoxical: you have to be capable of using AI whilst remaining responsible for its results.’

The momentum AI is gaining at times wipes out the limits of these technologies, which should push us to think in different ways. In fact, AI is empirical, but it is not a question of the same empirical knowledge as that of a human being, continues the Doctor of sociology. ‘We generalise situations on the basis of very little information and compensate for our gaps with our sensitive knowledge of the world. But, unlike the machine, a human being is bad when it receives too much information. The machine, for its part, is not effective with a little information, but with a lot of data it becomes very effective. The current issue is understanding how to get the two empirical knowledges to interact. AI will not mean an increase in productivity through the automation of tasks, but instead an increase in quality by means of better interaction between humans and machines. Through positive externality, we may see gains in time and productivity, certainly. But that should not be the objective aimed for from the outset.’

* The first name has been changed.

To continue our reflection on the technological revolution engendered by AI in the world of work, kingkong offers you an interview with Yann Ferguson in its unabridged version. A Doctor of sociology at the National Digital Sciences and Technologies Research Institute (INRIA), visiting researcher at the CERTOP (a French Research Center on Work Organizations and Policies) at the Université Jean Jaurès, Yann Ferguson is also the Director of Science at LaborIA. A research laboratory dedicated to AI and created by the Ministry of Labour, Full Employment and Social Integration and the INRIA in November 2021.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.