Are the major video game trade fairs in danger of dying out?

Article author :

A few days ago, Gamescom, the largest trade fair in the video gaming world, was in full swing in Cologne. On site, hundreds of thousands of fans were able to discover and test out the sector’s most recent new arrivals. But whilst the video game industry seems to be in robust health, certain events of this type appear to be suffering, even ebbing away… And what if, eventually, it turns out that it is the entire panoply of trade fairs which is in the process of dying out?

1,220 exhibitors, 63 countries represented, 33 pavilions, 230,000 m² of exhibition space. But first and foremost, close to 320,000 visitors over the span of five days. Gamescom has never appeared to be thriving to such an extent as this year. The largest trade fair in Europe dedicated to video games has pulled in the crowds, having made their way to the event to try out the latest video games, presented by the leading publishers such as Microsoft Xbox, Nintendo, Sega and Ubisoft, but equally games produced by the ‘indies’ (independent studios, often less ambitious than the big names, but pretty original, nonetheless).

We were there. And it was really something to feast your eyes on: grandiose stands, such as the one dedicated to the new strategy game, ‘Warhammer: Age of Sigmar,’ whose décor was no less than a small, yet full-size Medieval fort. Or the one for the new ‘The Crew Motorfest,’ assembled by the French publisher Ubisoft, which had quite simply arranged to have delivered to the fair a genuine, brand spanking new, latest model Lamborghini Gallardo for the occasion. And what about the one concocted by the Chinese HoyoStudio, including a giant robot, a specific boutique for their ‘in-house’ goodies, and dozens of cosplayers, people paid to parade around, dressed and made up as characters from the various games presented by the studio.

In short, a huge colourful party, ultra-hectic and excessive … and yet, for some observers, such as Corentin De Clercq, the proprietor of the Wallonia-based Little Big Monkey Studio, attending the event to do business, these levels of ostentation are on a lower scale than in previous years: ‘I noted that the Gamescom stands, even though they are still impressive, are less so than in earlier editions. It has to be said that they obviously cost an enormous amount of money, as is also true of handing out goodies, having people on-site, etc. For the publishers who budget for such things, it’s a massive outlay, and any returns on investment are far from guaranteed.’

Singing from the same hymn sheet is Domenico Laporta, a narrative designer and the head of new media at Wallimage. He has been attending trade fairs for 20 years, and he has already seen editions more impressive and excessive than the present iteration: ‘I remember the massive buzz when GTA 5 was announced. The same thing when the CD Projekt Red studio launched Cyberpunk, a good few years before the game was released; that was also crazy. Somewhere along the line, Nintendo even organised a Mario Kart competition in one of the halls, projecting animations onto the floor. All in all, there have really been some pretty incredible events here. But at the moment, we don’t really have that. The opening night is still a bit epic, but ide even so less than it was previously. And then, it must be said, everything is in German. It’s quite odd. Even the presentations for international games are made in German. So it remains quite local, produced for a specifically German and not necessarily international audience.’

But to understand the reasons for the progressive changes the Gamescom paradigm is undergoing, and by extension the other major trade fairs, we must, first of all, review the reasons they were organised in the first place, and their incredible success until now.

Trade fairs, large showcases for a booming industry

Born, in point of fact, at the end of the 1970s, the video game industry went through a rapid expansion, tugged sharply along by evolving information technology, which enabled it to offer increasingly developed and ambitious games.

Although it was still quite some distance from the professionalisation it is marked by today, the industry nonetheless experienced a significant boom and a first-watershed moment in the mid-1990s, with several leading companies involved in the race for consoles (Sony, Nintendo and Sega), an ever-expanding range of games for home computers and the expansion of specific development studios geared to this type of media. And yet, at that time, no trade fairs or events were dedicated to the sector.

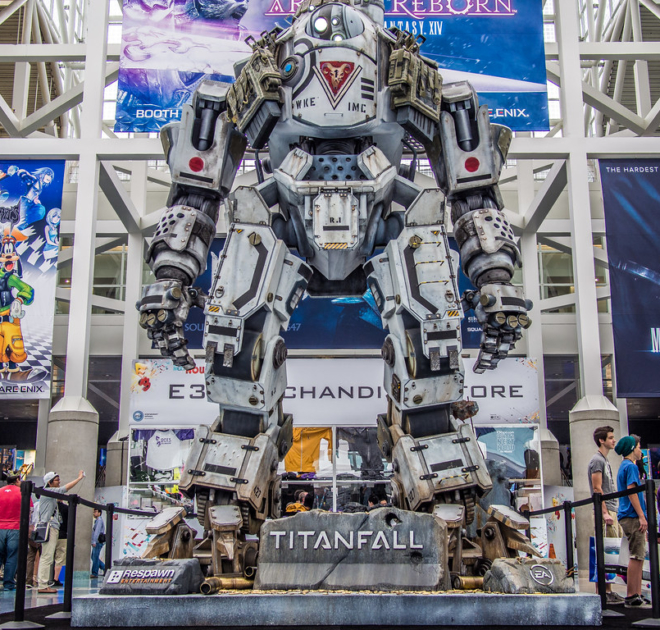

It was to make up for this lack that the Electronic Entertainment Expo, better known by the shorter moniker E3, made its first appearance in 1995, with Los Angeles acting as host. It was an immediate hit, with around 50,000 visitors for the first edition. And this success would only grow, transforming E3 into the industry’s annual meeting point, with constantly expanding stands, the presence of all the major publishers, lectures and games presentations which increasingly came to resemble flamboyant and always more spectacular shows.

But the Americans were far from being the only ones to have grasped the value in holding such ritual gatherings dedicated to video gaming. Across the whole world, other similar events sprang up, notably the Tokyo Game Show in Japan, inaugurated in 1996 at the very heart of the Land of the Rising Sun’s capital city, and the Game Convention, launched in 2002 in Leipzig (Germany), of which the renowned Gamescom has been the natural successor since 2009. And that is without listing the small gatherings and groupings of developers such as the Game Developers Conference – or GDC for those in the know – which had existed previously but benefitted from the explosion of interest to expand to the extent of becoming leading benchmarks in this field.

Apart from this audience aspect, these trade fairs above all enable encounters between the sector’s professionals. And this ‘B2B’ aspect could not be more important, as Domenico Laporta explains: ‘These fairs allow professionals to go to the exhibition site, to meet important people in the sector. You have a drink together, go to a restaurant, you have a discussion which goes beyond the scope of your game. And you remember all of this… For my part, there are people I met at Gamescom in 2007 with whom I am still working with today, in other words, almost 15 years afterwards. At this level, it is undeniable that human relationships remain vital, even in video gaming, which is, should we need reminding, a completely disembodied digital medium.’

Evolution and turbulence

At the beginning of the 2000s, the various trade fairs worldwide offered ever larger stands, ever more impressive shows. The goal: to attract people through this excess, but also to fill in for the lack of visual finesse offered by the games of the period, whose technology did not allow what we are used to experiencing today. ‘It was only the first baby steps for 3D graphics, and we had an aesthetic quality which was still quite poor and, as a result, the publishers had to display theatrical bluster to compensate for a visual aspect which, once you started the game at home, was quite unimpressive. Therefore, inevitably, at the trade fairs you had fireworks everywhere, big visual shows, incredible décor, gigantic screens, etc.,’ explains Domenico Laporta.

But this splendour came at a price. And it was a very expensive one. For E3, you were talking about 5 to 10 million Euros for a stand. A fortune. The same goes for the studios, who were having to pay exorbitantly for their participation, as Virginie Maréchal from the Belgian Clever Trickster Studio explains: ‘For example, the GDC necessitates a certain cost. Registration is between 350 and 2,300 dollars depending on access, the hotel costs 1,000 Euros for a room per week, flight tickets cost more or less 1,500 Euros. If there is a group of you going, you have to do the sums. It works out at a very high price. It only really has any value if you actually have a project to put on show, if at all.’

From 2006 onwards, the major players of publishing began to select certain trade fairs and to no longer appear at others. A situation which harmed the sector, including E3, which for the first time was faced with a genuine threat to its survival.

In such circumstances, the organisers attempted to adapt. Less shows, more room for negotiation for professional stakeholders, and presentations of games which became more like press conferences than disproportionate shows.

The outcomes of these changes were mixed. E3 blew hot and cold, first reverting to a very standard and more intimate event (scarcely 10,000 visitors in 2007), before once again offering a more expansive package starting from 2009. The other trade fairs managed to maintain greater consistency in terms of the numbers of people attending, but were also having to cope with withdrawals from several of the industry’s key publishers.

Especially as a new threat appeared after the 2010s: the development of online video streaming. Gradually becoming commonplace, this new kid on the block allowed publishers to offer their own presentation events live on screen. And it was Nintendo which got the ball rolling, with the first Nintendo Direct in 2011.

This format is very advantageous for the heavyweights in the sector, as Corentin De Clercq explains: ‘Apart from the financial aspect, the problem of these trade fairs for the publishers is the deadline they establish. They have to be ready, or in any case have something to showcase if they want to make major announcements. And sometimes these deadlines don’t fall at the right time. And this therefore forces them to rush, to harry the studios they are funding and run the risk of bringing out something which is not ready. A real gamble, when you know the extent to which a bad buzz can damage a game’s reputation. It is for that reason that the majority of the big publishers today have their own presentation fair, which takes place online. Because of this they not only have control over the deadline, but also over the content and the choice of how it is displayed.’

The COVID disaster and the death of E3

The other big publishers followed suit. Microsoft launched its Xbox Showcase, Sony its State of Play. The practice became standard in the industry. And no-shows became more and more regular over the years, much to the displeasure of the trade fairs.

In this already difficult context, an oppressive leaden weight would darken the prospects of the organisers. It went by the name of COVID-19. At the beginning of 2020, the pandemic struck across the entire planet, the economy ground to a standstill, and gatherings of people were forbidden. And obviously, E3, Gamescom, Tokyo Game Show, GDC and all the others were purely and simply cancelled.

The same thing occurred in 2021, a year during which despite everything several tried to adapt, by offering online versions of their trade fairs. Moreover these ‘events’ did not perform too badly, given the situation, but once again demonstrated that the sector can do without major physical events to keep operating, and that numerous studios even prefer this type of ‘online’ format, as Corentin Le Clercq confides. ‘I have to say that I really enjoyed the editions during COVID, which took place solely online. It allowed people to simplify things, it was easier to see directly if there was a common link between the studios and the publishers taking part. And in terms of costs, it was obviously a lot cheaper for everybody!’

The COVID-19 pandemic has in any event left a deep impact, of which the most significant is the death of E3. Whilst it was supposed to return in 2022, the American trade fair had to contend with a wave of the big names of gaming cancelling their participation. First of all, Sony, then Nintendo, then Microsoft. It was the straw which broke the camel’s back for the organisers, who threw in the towel.

In 2023, it was once again announced with great fanfare that the star of the trade fairs was making a comeback. But in vain. Faced with another no-show on the part of nearly all of the sector’s major actors, the assessment by ReedPop and the Entertainment Software Association brooked no argument: ‘Our decision turned out to be difficult … but we had to make a necessary choice for the industry and for E3. We understand that some companies would not have been able to make playable demos available to the public and that resource issues would have turned E3 into an insurmountable obstacle.’

But worse still was the follow-up to the press release issued by the two companies, announcing that they were ‘reflecting on the future of E3’. A form of words which seems to definitively sound the death knell of what was the largest gathering of the video game sector in the world.

A large question mark over the future

Whilst E3 has doubtless definitively taken its leave, the other major trade fairs have managed to keep going, and even flourished once the global pandemic had faded.

This year’s Gamescom, for example, did not achieve pre-COVID figures, but it despite everything performed well, above all in terms of its attending public.

But this brighter spell remains fragile, and even if the figures put forward seem promising and reassuring, the reality on the ground should be taken with a large pinch of salt, as Domenico Laporta explains: ‘having been there, the GDC this year was no longer the GDC as we knew it previously. It is visible to the naked eye. There are very empty spaces. And here at Gamescom, you should see how Netflix occupies an enormous pavilion even though it has no games to sell… What they are targeting is the creation of TikTok and Instagram content thanks to the public and well-designed stage sets. That is how they occupy the space. And that certainly means that the prices for the stands has dropped, which is a sign. In addition, the stands are now reserved for many years. For Netflix, people are talking about a period of ten years. So we can deduce that the template may change a little… Gamescom risks resembling a hotchpotch, of becoming something along the lines of the San Diego ComiCon… An event at which you are more likely to find many cosplayers, an event which is more ‘celebratory’ than akin to a genuine business platform’.

On the subject of business, it seems likely that there will be less of it. But for its part the audience appeal remains an important factor for Corentin De Clercq: ‘for the public, this type of event remains an excellent one to be able to try out new games as part of a preview showing, to get an idea of the various new licences which will be coming out. But even at this level, things are changing. We now have the opportunity to gain ‘early access’ and beta versions of games. Which means that you no longer need to go to the event site to discover new things as part of a preview showing. But, on the other hand, there is still the atmosphere around the various stands, which are gigantic and very impressive. There are also all of the goodies to be collected, and that’s something quite special for the real fans.’

Enough to keep these enormous ocean liners afloat? That remains highly uncertain. Especially as the industry is gradually becoming saturated, and producing successful games is becoming more and more difficult to achieve.

A new metamorphosis is thus quite probable: ‘we shouldn’t be surprised in the coming years if E-sports appropriate this type of event, with competitions. Bring them on, I say, and let them be a lot more events based, much livelier. Because the public turns up in numbers, it is very keen on them… On the other hand, one thing is certain; the professionals, for their part, will attend less and less.’

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.