The Guerrilla Girls, the feminist collective baring its teeth at the art galleries

Article author :

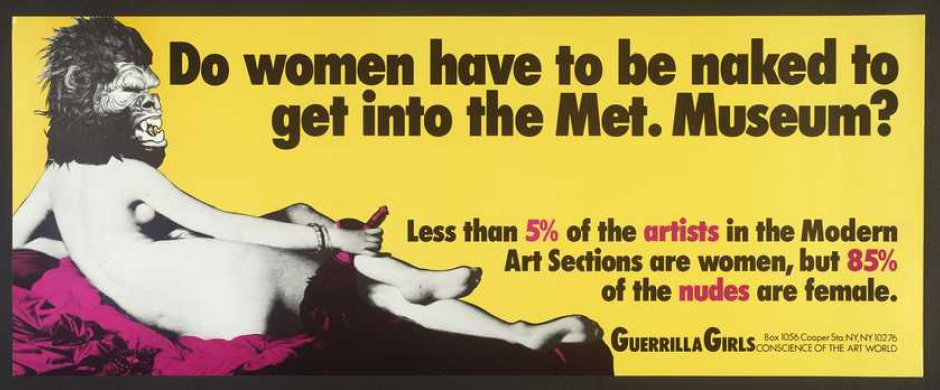

‘Do women have to be naked to get into the Metropolitan Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.’ Behind this globally well-known poster are hidden the Guerrilla Girls. Since the 1980s, this collective of female artists has been fighting the gender disparities in the world of contemporary art.

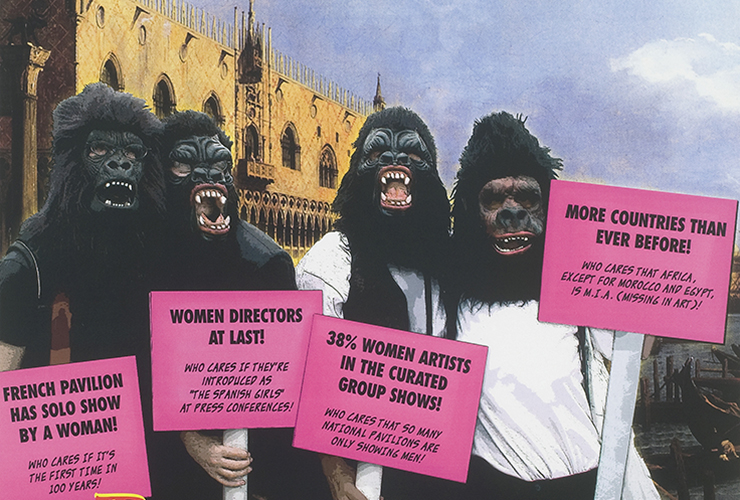

The Guerrilla Girls describe themselves as ‘the conscience of the art world, counterparts to the mostly male traditions of anonymous do-gooders like Robin Hood, Batman, and the Lone Ranger.’ They have produced over 80 posters, printed projects and actions that expose sexism and racism in the art world and culture at large. Their weapon of predilection: a provocative humour which has drawn the attention of the most important art galleries.

The birth of an international movement

In the spring of 1985, seven women launched the Guerrilla Girls in response to an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York the previous year. Entitled ‘An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture,’ the showing found space for solely 13 women amongst the 169 artists represented. The exhibition claimed to represent the most important painters and sculptors of the era. It nevertheless featured only eight artists of colour, all of them men.

Comments attributed to the curator, Kynaston McShine, during the opening night highlighted the explicit gender bias of the exhibition and of the art world at that time. In an interview given during the inauguration, he stated that ‘any artist who wasn’t in the show should rethink ‘his’ career.’ In the interview, given in English, McShine used the masculine pronoun ‘his,’ clearly demonstrating his biased view of what the epitome of the classic artist was.

A deceased artist’s name as an alias, a gorilla mask… The identity card of an anonymous activist

When the movement was still in its infancy, its founders were all white women. They spread their messages by means of posters they glued up in Manhattan city centre, in particular in the SoHo and East Village districts which accommodated their initial target: commercial artists and galleries. One year after its creation, the group broadened its focus to include racism in the art world, thereby attracting artists of colour. Several criticisms were nevertheless levelled at the collective, primarily owing to the lack of diversity amongst its members. Their art was considered exclusive to white feminism. Zora Neale Hurston, an Afro-American writer, anthropologist and activist, deplored the fact that the membership of the Guerrilla Girls was ‘primarily white,’ and largely reflected the social class of the art world they were criticising.

Despite their wearing a mask to hide the identities of its members, some observers attribute interest in the Guerrilla Girls to the fact that the leaders, known by their assumed names, ‘Frida Kahlo’ and ‘Käthe Kollwitz,’ were both white women. ‘Frida Kahlo’ was furthermore castigated for her appropriation of the name of a Latin artist.

Questioned about their masks at the beginning of the movement, the members responded:

‘We were Guerrillas before we were Gorillas. From the beginning the press wanted publicity photos. We needed a disguise. No one remembers, for sure, how we got our fur, but one story is that at an early meeting, an original girl, a bad speller, wrote “Gorilla” instead of “Guerrilla.” It was an enlightened mistake. It gave us our “mask-ulinity.”’

Powerful works which quickly drew the attention of the museums they were calling out

One of the hallmarks of the art of resistance used by the Guerrilla Girls is their sense of humour. ‘We quickly discovered that humour gets people involved. It’s an effective weapon,’ stated one of the members in an interview in their first book, ‘Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls,’ published in 1995.

The poster, Do women have to be naked to get into the Metropolitan Museum?” was created in 1989, after the Guerrilla Girls had visited the museum in question, counting the quota of female artists in comparison with the female nudes on display in the institution. Their discovery: ‘Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.’

The poster shows ‘La Grande Odalisque’ wearing a gorilla mask. To reach their audience, the collective rented advertising space on the New York buses. But the rental company quickly cancelled the contract, stipulating that the image was too suggestive, and that the young woman represented seemed to be holding something other than a fan in her hand.

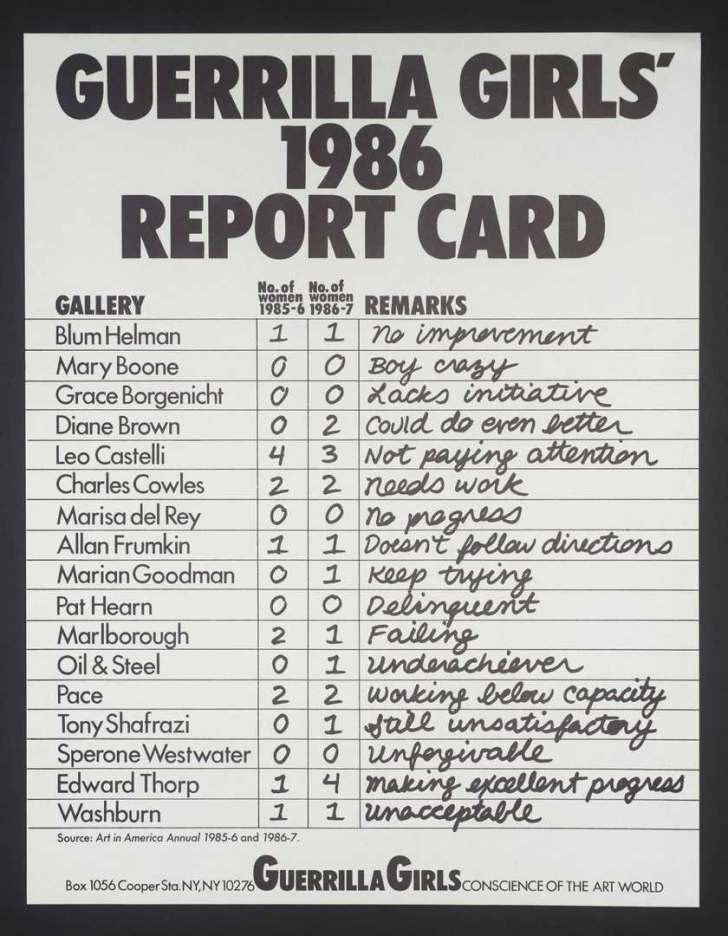

The Guerrilla Girls 1986 Report lists 17 galleries in comparing the number of women artists exhibited between 1985-6 and 1986-7. The poster, like others in their portfolio, Guerrilla Girls Talk Back, borrows aspects from advertising and publication in improvised ways. For the most part, they were glued up at nighttime in the streets of New York.

At the end of the 1980s, the Guerrilla Girls were very active, distributing their posters throughout the country. Reactions to their art were mixed but, on the whole, they gained a certain popularity. Their role in the art world was consolidated when several major organisations supported their cause. In 1986, the Cooper Union held several round tables and discussion panels with art critics, art dealers and curators, to discuss suggestions regarding reducing the gap between the sexes in the art milieu. One year later, the independent art space, The Clocktower, invited the Guerrilla Girls to hold a protest event against the Whitney Museum’s Biennale of American contemporary art, which the collective named Guerrilla Girls review the Whitney.

A system dominated by white men

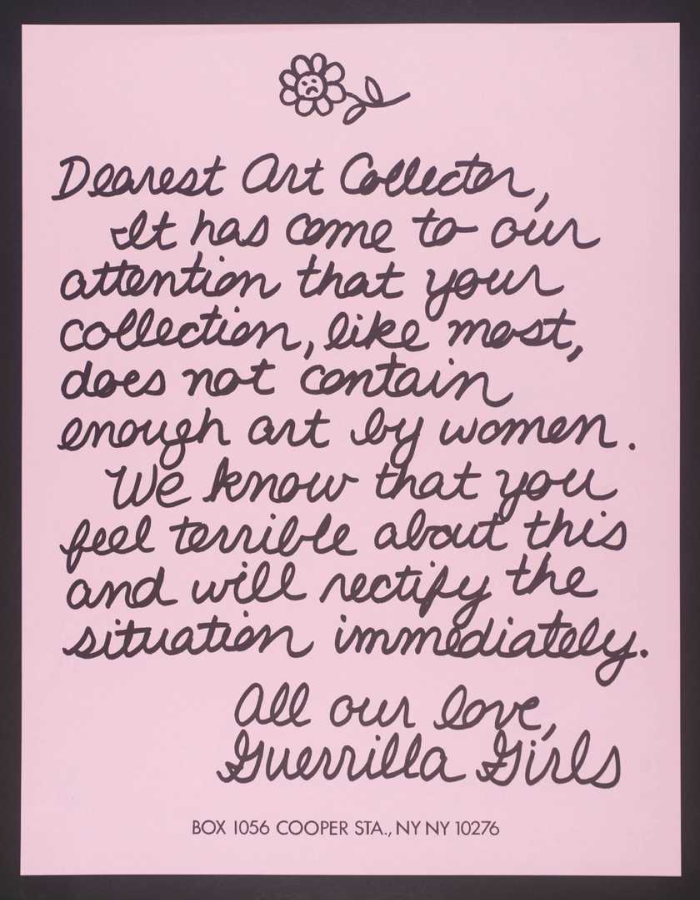

The big question remains: who is responsible for the discrimination against women in the art world? The Guerrilla Girls are of the opinion that it is mainly rich white men: ‘the museums depend more and more on gifts of money and artworks from very rich collectors – and these collectors are generally white men, who primarily collect works of art created by white men.’ Consequently, the museums are no longer documenting the history of art, but that of wealth and power, the activists argue.

Not everyone agrees as to the magnitude of the impact the Guerrilla Girls have had on the lack of diversity and the explicit gender biases operating in the art world. The group is nevertheless credited with having provoked a dialogue and drawing attention to the problems. One thing is sure, however: standing up for a just cause, whilst wearing a gorilla mask. At kingkong, we wholeheartedly approve.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.