Tanaland, this imaginary world for women questioning their online experience

Article author :

A new trend has inundated TikTok: the creation of Tanaland, an imaginary country reserved solely for women. Its goal? To fight against online sexist and misogynistic comments.

It all started in September 2024. Sali Matou (@hadja_bh2), 18 years old, is in the final year of her secondary studies in France. One evening, she decided to post a humorous and ironic Reel on TikTok. She filmed herself performing, suitcase in hand and slamming the door. On the video can be read the words: ‘I am leaving France and off to Tanaland, as we are all whores’ (Editor’s note: ‘tanas’ in French). Without intending to, she had just created a trend which, in light of its success (1.7 million views), mirrors a reality: women and minoritised people do not feel safe on the internet and the social networks.

@hadja_bh2 ♬ son original – ⠀

‘It is a totally imaginary fictional country which has been created for women subjected to cyber-harassment on the internet, as on TikTok, for example,’ explains the young woman in an interview given to the French media outlet Fraiches.

Her idea of leaving everything behind to go and live in Tanaland was shared by a large number of users. Several particularly highly followed influencers such as Paola Locatelli, Too Much Lucille and Polska joined the movement. ‘In September, there were a lot of guys commenting on women’s TikTok pages and calling them “Tana” for no good reason, for example just because they were wearing dresses which in their opinion were too tight-fitting, or quite simply because they were not doing what the men considered “acceptable” on the social networks,’ continues Sali Matou.

Turning an insult into an advantage: a retaliation tool?

The word ‘Tana’ makes direct reference to the Spanish word ‘putana’, in other words, whore, clarifies the creator of Tanaland. ‘“Tana”, it’s a ploy. As it is forbidden to say “whore” on the platforms, men have therefore found a work-around means of being insulting when commenting on videos by women. They call them Tana. And the word is being used sweepingly on TikTok. A woman who puts on make-up, she’s a tana. A woman wearing leggings, she’s a tana. A woman with a strong character, she’s a tana. Any excuse is a good one to call women tanas,’ points out this Radio France article. In short: these men, considering the word ‘whore’ to be an insult, use it as a misogynistic putdown, which has gone viral on TikTok and is being posted in the comments on videos produced by women. It is used to belittle the way they speak, the way they dress, the way they behave and more generally their lifestyles.

@paolalct ma ville preferée 💕

♬ son original – ⠀

With Tanaland, TikTok users have turned around the stigma they have been the victim of. Melissa Amneris, a content creator and presenter of the DEEP podcast, emphasises the point on Konbini: ‘they have fought against online misogyny and cyber-harassment by reappropriating oppressive terms to turn them into symbols of strength and unity.’

What does the Tanaland phenomenon say about the position of women online?

Tanaland therefore seems to have become a Utopian safe place consisting of 18 million citizens. A country which has been entirely fabricated by means of AI, with its own flag, its own government, its own charter and even its own anthem. An imaginary world in which sisterhood and female empowerment are the watchwords. A fictional country pushed to excessiveness whilst at the same time reproducing gender archetypes (for example, the use of the colour pink).

Florence Hainaut, a freelance journalist specialising in cyberviolence issues, is delighted by the emergence of this new trend: ‘both from a feminist perspective and from a digital perspective. What is currently happening on the internet is depressing, the existence of Elon Musk is depressing, but I consider this Tanaland trend to be really positive. It illustrates that the internet can also be a site of immense creativity, a site of feminist resistance. These users have in their own way inverted the stigma, they have done so instinctively […] Tanaland also shows that resistance can be joyful, funny, confrontational, whether we are aged fifteen or we have been campaigning for years.’ For the journalist who, together with Myriam Leroy, has produced a documentary on the subject, ’#salepute’, and who has published a book called Cyberharcelée, 10 étapes pour comprendre et lutter (Editor’s note: Cyberbullied, 10 steps to understand and fight back), the creation of Tanaland is political. ‘Through this trend, I think it is women expressing a sense of being fed up. “We are not cannon fodder, we are not there to be insulted by guys, we have had enough of it.” This approach is, in my opinion, really political. […] They do it with the codes of their generation and above all with a lot of humour.’

A similar opinion is held by Anaïs Loubère, the founder of the Digital Pipelette agency, who in the French daily newspaper l’Humanité argues that: ‘Tanaland is women content creators’ response to sexism. Obviously, we have no place in your society because we are never good enough, so we are going to create this world which will be for women only and it will be a safe place where we will finally get some peace.’

The essayist Vincent Cocquebert adds to the assessment in the columns of the ADN media platform: ‘with the Tanaland phenomenon, it is almost as though women are seceding within the virtual world. We have moved on from a suffered gender segregation to a carefully selected gender segregation, and it’s very telling.’

According to the UN, 73% of women worldwide are subject to violence on the internet

Launched in France, this trend particularly resonates in view of the latest figures revealed by an IPSOS investigation. Thus, in 2022 in France, 84% of the people who experienced cyberbullying on social networks were women. Globally, the UNRIC (United Nations Regional Information Centre) explains in an article that in 2015, the UN estimated that 73% of women worldwide experienced violence on the internet, in particular harassment. And it specifies that: ‘in 2021, according to a study carried out by The Economist Intelligence Unit, this figure is said to have risen to 85%, the COVID-19 pandemic having had its impact, and the situation is doubtless worse today.’

Violence which has serious consequences. In 2018, Amnesty looked into the issue by focusing on the social network Twitter (today owned and renamed X by Elon Musk). The result: female victims of harassment were changing their behaviour on social networks, by for example not publishing their opinions on certain subjects. The Amnesty press release also explained that women of colour, of an immigrant background, LGBTQIA+, with disabilities, or belonging to an ethnic minority, were even more targeted.

To combat this cyberviolence, the community association milieu time and again recommends education at the earliest age, but also and first and foremost legislative and criminal advances. Initiatives are beginning to be implemented. Recently, CyberSafe was created. It is funded by the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, in collaboration with FATSABBATS and S-COM. ‘It’s a rapidly growing project which gathers testimonies in order to create tools to enable the victims of online violence related to racism, sexism and LGBTQIA+phobia to obtain assistance to defend themselves,’ points out this article in Les Grenades (RTBF).

In reaction to Tanaland: the creation of Charoland

Sali Matou, the young user behind the trend confides (again in the media platform Fraiches): ‘I received a massive amount of support but also threats […] I just keep in mind the support and then it doesn’t make me afraid.’

In fact, whilst the trend has been an unqualified success, it has also been vehemently criticised by men on social networks. Some of them have even decided to create their own country. A Radio France article from the ‘Un Monde Nouveau’ podcast adds: ‘Some men express their support for the women, ask for a visa, offer to act as security guards on the country’s borders, beg to be accepted … Others, as a reaction, have invented “Charoland”. A virtual male country in which they can continue to treat women in whichever way they choose, in other words, the cyberspace such as it is today, in fact … unfortunately.’

For Florence Hainaut, the birth of Charoland was a foregone conclusion: ‘I think their response by way of creating Charoland could be boiled down to: “our world, you are a part of it, where women are sexually objectified […] where you serve us cocktails.” In my opinion, Charoland is not presented as a response to Tanaland, it is a masculinist response to a feminist wake-up call. Therefore it is not by any means the counterpart to Tanaland. Tanaland is emancipation, Charoland is domination,’ she concludes.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

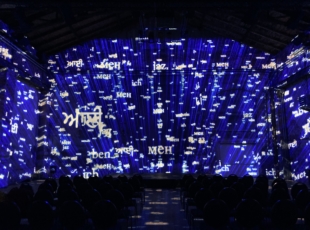

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

NUMIX LAB 2024: creating bonds and building the future of digital creativity