When streaming floods European production: towards a cinema produced by business schools?

Article author :

Outsiders to the European audiovisual landscape some ten years ago, streaming platforms are nowadays an integral part of the film and series industry. From initially being merely distribution media, these services have progressively become (co-)producers of original content, signing off on rising numbers of European ‘in-house’ creations. A sweeping change which has led to certain cinema professionals grinding their teeth.

In his essay, ‘Netflix, mass-produced alienation,’ published at the end of 2022, the French producer and journalist Romain Blondeau offered quite an alarmist overview of audiovisual production in the era of platforms. He raises particular concerns over the standardisation of the content produced by these international giants, which in his opinion are responding to commercial imperatives to constantly capture attention, thereby completely eschewing any artistic or reflective considerations. He condemns an ever-growing standardised framework imposed on the teams working on these products, both in terms of scriptwriting and of directing, and points out the risk European cinema is running of seeing these practices develop and become more and more widespread. A few weeks ago, in an interview for France Culture, French screenwriters for their apart highlighted certain abuses in the platforms’ writing practices. Observations also reported by film crews in charge of these projects.

Requiring platforms to contribute to local audiovisual production: European obligations

Europe can boast of having a rich audiovisual culture and a varied and cutting-edge cinematographic practice. Needing to react to the emergence of the platforms and the surge of international content on the European market, the European Union has legislated to guarantee a certain protection to European cultural diversity, on the one hand, and to its audiovisual industry on the other. In practical terms this means that for VOD platforms, in Europe, 30% of the content of their catalogues must consist of European works, at a minimum. The platforms are also required to showcase this content. They are, furthermore, and above all legally obliged, in several countries including France and Belgium, to contribute to local production, by investing a percentage of their revenues in the country’s audiovisual production via, among other means, the co-production of national content. Increasing numbers of ‘local’ series and films branded with the logo of Amazon, Netflix and others, co-produced with European companies, are thus flooding our (small) screens.

Whilst this measure is evidently advantageous in that it constitutes a significant source of funding for local audiovisual industries, whilst ensuring that content benefits from large-scale distribution, a red flag may be raised about it in terms of the practices and formats thereby created, which can at times diverge drastically from national standards to meet the wishes of the platform which is commissioning them.

An American-style vision: towards made-to-order films?

‘The platforms have a specific system and a way of doing things,’ explains Laure Monreal, a film direction first assistant, who has just been involved in two consecutive French projects for Amazon and Netflix. ‘It involves working from an American-style perspective, one heavily based on marketing.’

One of the defining characteristics of projects steered by Amazon, Netflix and their like is in particular the central role entrusted to the production team, which governs the decision-making process, whereas here in Europe those decisions are usually left to the director. ‘The way we do things is increasingly resembling made-to-order films,’ points out L. Monreal. In classical film or series production processes, the person who directs has significant power over casting choices, team leaders, set design, etc., which enables that person to sign off on the content created. In this case, it is the production team which holds the reins, working very closely with the platform. A template which might ring a number of alarm bells, especially in terms of creative freedom and the artistic directions taken.

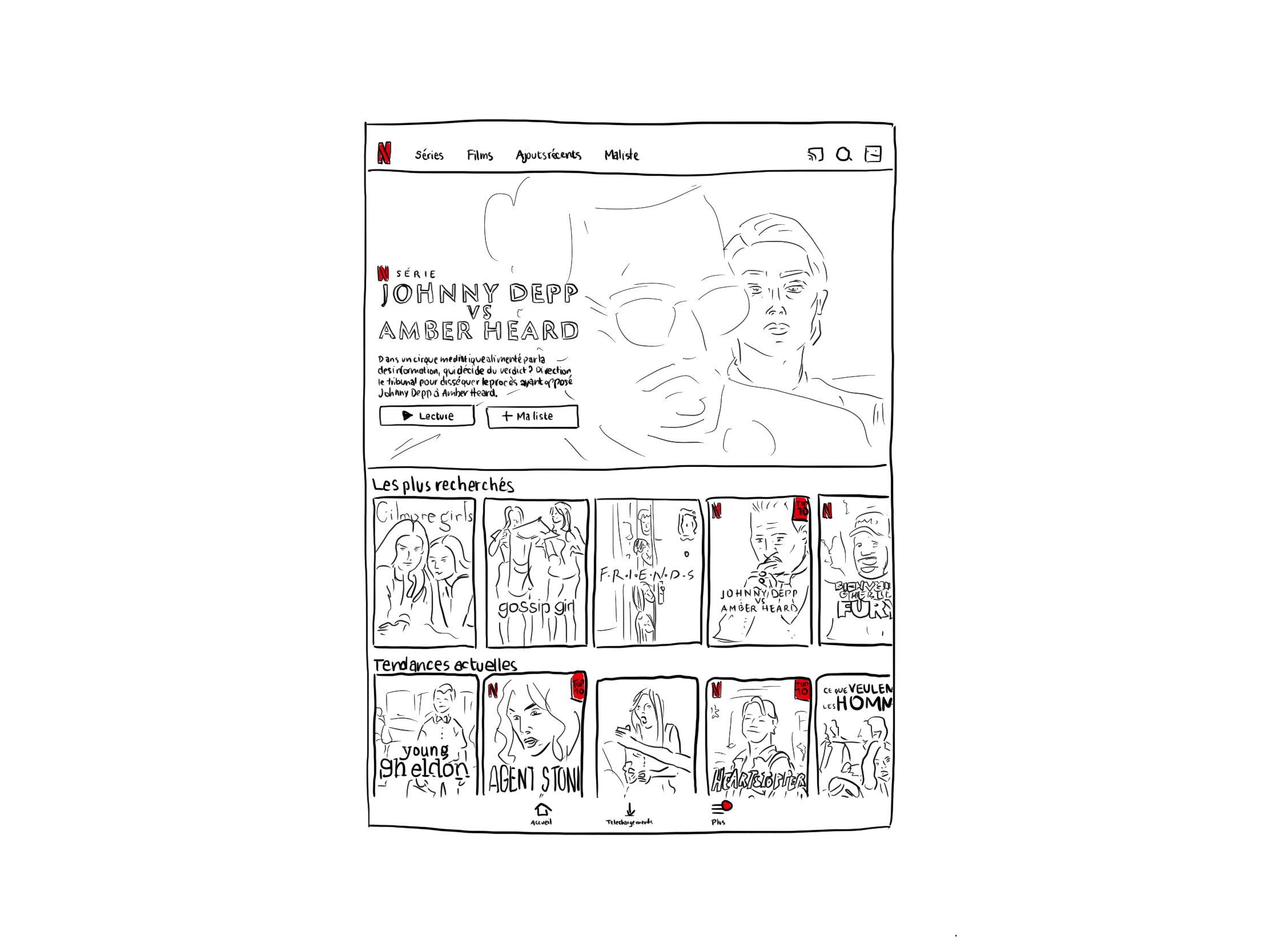

A film in the kingdom of media buzz

Because the goal of these platforms, whether the idealists like it or not, is not to promote cinema with a capital ‘C’, but to broadcast this content to the largest possible audience. And to get noticed amongst the thousands of titles, you need effective formats, names which carry weight, images which are exportable. Several observers have highlighted the fact that the managers of the platforms’ creative teams are increasingly graduates of business schools rather than holders of cinema degrees. From this arises a very commercial approach to the projects in question, one which occasionally resembles more the practices at work in advertising than in fiction. ‘What has become systematic for example, and which I had never come across previously, is the system of mood boards. With the platforms, you make a mood board for everything: the set, the light, the make-up, etc. We are moving closer and closer to the type of business meetings held by major companies.’

An approach which, in itself, might be understandable, but which raises several concerns when, on certain projects, disconnected from the actual situation on the ground, it seems to become the main component of the equation, to the detriment of the practical production of content. Certain names seem to be chosen more for their ability to sell (themselves) than their technical skills: they are enlisted by the platform for ambitious projects, but in underestimating the resources necessary. The platforms approve them without knowing enough about the realities of filming and once the project gets on-site, these problems come to the fore: significant overruns in the work plan, editing issues, necessary reshoots, etc. Problems common to every production, but which here seem to be exacerbated, presumably due to the people in charge misunderstanding the realities on the ground.

These difficulties may be explained, according to several commentators, by differences between the United States and Europe in terms of organising teams (very hierarchical on the one side, more organic on the other), involving filming practices which are occasionally diametrically opposed. Hence there arises the need for chameleon profiles, who are assertive and know the two contexts inside out, and are capable of usefully establishing a link between the two.

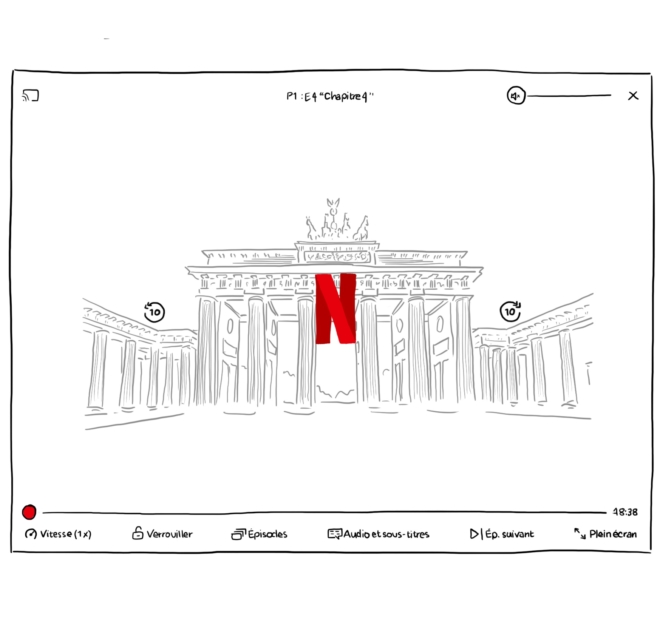

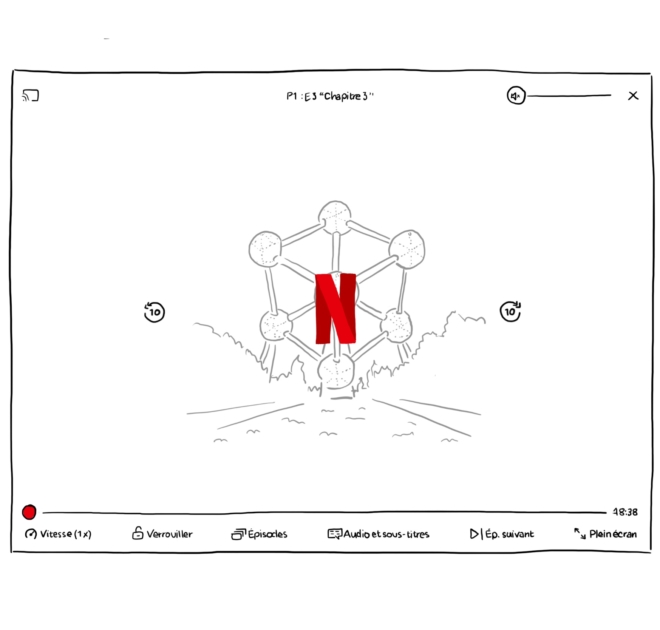

Glocalisation: producing locally to export everywhere

In terms of content, a number of people have raised red flags over the uniformisation of plotlines and the clichéd character of the local references depicted in these national co-productions. Series such as Lupin in France, la Casa de Papel in Spain, or Squid Game in South Korea, have for that matter had greater success abroad than in the countries they were produced in. They are in line with a trend, particularly visible at Netflix, called Glocalisation: the act of producing local stories, but developed in such a way to satisfy a global audience. On the menu, a shrewd mixture of typical landscapes, local representations geared to a (very) touristic perspective, and conversely a very universal plotline, which can speak to an international viewership. A winning formula economically speaking, and which will thrill non-European audiences keen on baguettes, berets and striped jerseys, but which raises concerns when one thinks of the creative and cultural wealth of each country, which seems to be completely sidelined to the benefit of a blockbuster vision of content, one which is very American, when all is said and done. Maintaining cultural diversity, you were saying?

And over here?

In Belgium, the number of co-productions working in tandem with the platforms is a great deal lower than in France, but should rise in the years to come owing to the ‘contribution to production’ measures coming into effect, and a probable increase in the stipulated ratios on the horizon. A challenge for our industry, as is underlined by Jeanne Brunfaut, Director of the Cinema and Audiovisual Centre, in an interview given to the CSA. This industry will have to find a balance between maintaining its freedom of creation and Belgian specificities, on the one hand, and the economic opportunities and mass distribution permitted by these platforms on the other.

We have the power of creation, so let us hope that it may navigate as effectively as possible between the different production pathways and emerge in all of its diversity. The platforms are a part of our lives, we are familiar with how they operate, how they produce and offer content. Binge-watching a slightly clichéd series from time to time does many of us the world of good, and that’s fine. Let us simply remind ourselves to also consume in other ways, to watch something that has been made differently (and consequently support these forms of creation), to go to the cinema, or to use alternative platforms other than these American giants. We are thinking in particular of arte.tv, which is gradually standing out as the European public cultural platform, or of in-depth streaming services such as the English outsider Mubi.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

NUMIX LAB 2024: creating bonds and building the future of digital creativity