The Namur Legal Lab, for start-ups in the digital domain

Article author :

As part of their Specialised Master’s in Digital Law at the UNamur, students offer small start-ups quality and free-of-charge legal counselling.

The legal difficulties and obstacles an entrepreneurial project has to contend with constitute one of the main failure factors affecting start-ups in the digital and new technologies sector. In view of such an assessment, for the students taking the Specialised Master’s in Law, focusing on digital law at the UNamur, it is a baptism of fire. They learn their future profession whilst offering free-of-charge advice to debutant start-ups which could not afford to pay for their own legal department. ‘It is the first time they have to face up to the real needs of an actual company, on the market. The Namur Legal Lab is a kind of transition airlock between studies and future professional activity, a springboard to working life,’ points out Camille Bourguignon, the coordinator of this special pedagogical project.

The initial idea of designing such a law clinic came from the United States, before being taken up within Europe and adopted, in particular, by the University of Namur. The first trials took place in 2015. At that time, the venture involved a mere handful of students who volunteered to assist four start-ups. ‘Given its success, this pedagogical project became a compulsory part of the curriculum in 2018. This has allowed more start-ups to benefit from legal advice. And the building up of a good pool of 80 of these fledgling companies located in Namur.’

Camille Bourguignon and her colleagues go looking for these small enterprises in well-known incubators in the digital landscape. In Namur, a close partnership has been created with the BEP (Economic Office of the Namur Province). And thus with TRAKK, a creative hub dedicated to the cultural and creative industries, and to the digital domain, to which it is intimately connected. ‘The start-ups offered aid by the BEP are already mature, with fully developed ongoing projects. In our opinion, that is important to prevent a start-up falling to pieces in the course of the Namur Legal Lab.’

Being immersed in the skills-base

In practical terms, the start-ups interested in the concept must apply by filling in a form. In it they succinctly describe their project. And are selected on the basis of the questions it raises in terms of digital law.

‘Are there vital questions concerning the protection of personal or medical data? If yes, we jump on it and away we go. In fact, it is typically this type of question which needs to be asked at the start of a project, and certainly not halfway through. Projects which are targeting the construction of an e-commerce website or a mobile app are also interesting: they give rise to questions as to a consumer’s right to information. Certain start-ups are considering registering a trademark: our students also have the skills to counsel them.’

The issues of the management of copyright, intellectual property, telecommunication, competition, the sharing of data which is not personal, or the law governing online platforms also have a special resonance within the Namur Legal Lab.

Two months of legal counselling

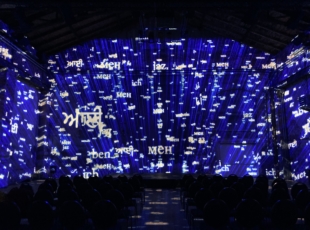

Whilst the students, teamed up in groups of three, are free to organize how they work with their start-up, the Namur Legal Lab establishes the foundations to enable the initial conversations to take place. Each year, along with TRAKK and the BEP, it arranges a launch meeting, the ‘kick-off’ in the language of start-ups, at the beginning of October. ‘We invite the start-ups selected to come to TRAKK to pitch their projects in front of the other chosen start-ups and the groups of students. Outside of the presentations, they meet their start-up for the first time, and ask the questions necessary to understand its project and to identify the legal issues they will subsequently look into,’ explains Camille Bourguignon.

‘In mid-December, we arrange another meeting at which the students orally present to their start-up, with the aid of PowerPoint, their recommendations in relation to the questions they have examined. Here are the problem issues of your project, here is the law which applies to them, here is how we apply it to your project. And here is the action plan to be implemented.’

The students provide concrete recommendations, but without delivering a proposal for a contract or a register, for example. ‘In other words, they provide a breakdown of what the start-up will have to do afterwards. The idea is thus not to encroach on the turf of the lawyers,’ specifies Camille Bourguignon, formerly a lawyer and now a lecturer and assistant within the UNamur’s Master’s in DTIC.

A rich first experience

What do the students take away from it all? ‘It’s the first time in their lives they have had to deal with people who have real legal needs concerning digital law. Up until then, they have only resolved theoretical cases. This experience is also pretty stressful for them: their recommendations have to be absolutely correct. They have to be juridically verified from every angle so that they do not provide the start-up with a false solution, as that could potentially endanger it.’

The students must also momentarily forget their jargon. It’s a question of employing a language adapted to the people they are speaking to. Of avoiding at all cost presenting legal concepts using words incomprehensible to non-jurists. ‘They thus discover the difficulty of making yourself understood. They have to find a balance between juridical rigour and a language which allows them to provide information meticulously but without it being obscure.’

Aid for Linkube participants

Another legal project has taken root at the Namur Legal Lab and the BEP within the scope of Linkube, an incubator for student entrepreneurs. For the students enrolled in the Specialised Master’s in Digital Law, it involves advising these young entrepreneurial shoots.

This time, it takes the form of a seminar, which they devise on a voluntary basis. When it is held, in December, the Linkube project owners with issues concerning digital law are invited to put their questions orally. The law students have to respond to them immediately.

The questions which fly thick and fast during the seminar are of a highly practical nature. For example, the young person who, to increase their visibility, sent out emails left, right and centre, and was wondering if they had the right to do so. Besides questions bearing on e-commerce, the GDPR and intellectual property, a number concern advertising on the networks and influencer marketing. ‘In addition to being useful for the entrepreneurs, the concept is educative and much appreciated by our students,’ concludes Camille Bourguignon.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

NUMIX LAB 2024: creating bonds and building the future of digital creativity