The music video in 2023: asset, relevance and evolution

Article author :

What is the place, the role and the relevance of the audiovisual media in a musical project? In what ways are artists, filmmakers and their teams adapting to the new tools and formats at their disposal? What initiatives are being developed to encourage the creation and distribution of Belgian music videos?

The music video, a shop window to a musical and artistic universe

Last June 9, the author-composer-performer ML unveiled her new EP, the sublime Ailleurs n’existe pas. A project with seven tracks, intermingling alt-pop and indie rock, carried by heady melodies and a lyricism which is simultaneously honest, poetic and honed. A fundamentally sincere music, therefore, reinforced with an aesthetic which hits the mark: striking colours, a 90s look, a curtain fringe and a hand-written logo, a human image which brings to mind Maggie Rogers, Angèle and Lou Doillon. This visual identity is to be found in every nook and cranny of the ML project, and in particular in her music videos: whilst the film of “Ressaisis-toi” places her on stage in a variety of settings – at times wearing a baseball T-shirt, a Walkman in her hand, her body spinning to the rhythm of the music in a Paris apartment, at others meandering in the changing rooms of a sports club donning a magnificent Fender Stratocaster – the one dedicated to “Crève d’ennui” transports us straight to the beaches and shingles, into the fields or alongside a stream, bringing to mind, without any filters or gimmicks, the freshness and spontaneity of this artist fully expressing her exuberance.

A music video is like a business card. It is often said that food is eaten with the eyes, and the same is true for music. As an artist, you need an artwork, photos, a music video to share your visual identity and situate yourself

Benoît Do Quang

‘The role of the music video, it’s above all to establish a setting. It’s a question of providing a certain light, a mood to your music,’ ML confides to us. She is spot on, as well: music videos, in the same way as record sleeves, the T-shirts sold after concerts or Instagram reels, are part and parcel of a global artistic approach, and enable a universe to be created around a music project. This opinion is also shared by Benoît Do Quang, a director of music videos, documentaries and adverts. ‘A music video is like a business card. It is often said that food is eaten with the eyes, and the same is true for music. As an artist, you need an artwork, photos, a music video to share your visual identity and situate yourself,’ he explains. Located at the perfect intersection between a work of art and a promotional tool, the music video thus allows artists to create a narrative, and to reach out to their public. A necessary – even essential – approach in an increasingly competitive industry, in which music projects are mushrooming at lightning speed. ‘Music videos have become indispensable. If you don’t make any, you may have the impression that your song just falls by the wayside,’ adds ML.

The music video, an unbridled artform?

‘Around ten years ago, I made a music video for my mates in Kennedy’s Bridge. Basically, I just had a thing which films. And as Orelsan says, if you want to make films, you just need something that films,’ adds Benoît. Without having any prior knowledge, we just put it together by making do with whatever was at hand: we built something to produce travelling shots with a wooden ladder from IKEA and rollerblade wheels because we found that it made it professional. Even though thrown together by messing around with very little in terms of means, the music video has played an essential role in the group’s career, as well as that of its director. ‘It was the beginning of the YouTube success story, and the thing got 10,000 views in one week. There were articles in the local press, etc. That led to my mates playing the Ardentes festival whilst they had only ever played basements in bars before. It was then that I became aware of the power of the music video: with very little means, with creativity and some resourcefulness, you can make things which have an impact and value.’

Benoît has been defending tooth and nail this art of improvising and problem-solving for several years now. ‘Thanks to technology, tools have become much more accessible. This democratisation has enabled people like me, who have neither any training or equipment, to be able to make music videos. Once that was established, there was a place for creativity and things which were more thrown together,’ he confesses. Nevertheless, as he accumulated experience and encounters with other people, the director has succeeded in professionalising his approach. ‘Now, we are moving into another era, and you can see that both in music videos as well as in the production: things are becoming more and more produced. I think we have seen DIY run its course: everyone goes one better each time, and now, when you watch the music videos for French rap, they are almost short films,’ he adds.

I think that all of these people who are doing DIY are only dreaming of one thing, having a budget

Maxime Pistorio

According to Maxime Pistorio, a director and co-founder of the Belgian music video VKRS, DIY is intrinsic to the video environment. ’25 years ago a music video was an impractical Heath Robinson contraption: it was very expensive, you needed lights, a studio, etc. Nowadays you don’t need anything. You can film with your iPhone and do the editing on your kitchen table (…) That said, I think that all of these people who are doing DIY are only dreaming of one thing, having a budget,’ he emphasises.

Money, the missing piece of the Belgian music video industry

Maxime has also hit the nail on the head: funding, that is what the Belgian music video industry is missing the most. ‘In Belgium, no-one makes a living from music videos,’ confesses Yoann Stehr, a director and the founder of the production company Super.Tchip. ‘It’s a very precarious economy: the majority of production companies which make music videos also make adverts, and for that matter it’s their main source of revenue. As for me, I begin with practically nothing, I have zero basic cash. Super.Tchip, it’s not called that for nothing.’ Three years ago, directors were finally afforded a glimmer at the end of the tunnel: the Wallonia-Brussels Federation has established some financial aid earmarked for professionals of the audiovisual world. The principle is a simple one: each year, a call for projects is launched. The projects presented are looked over by a commission, which allocates a grant of up to 20,000 Euros to the projects which are accepted. ‘It’s a wonderful initiative, I am really made up that it exists. We had been calling for such aid for a long time,’ adds Yoann.

What triggered me being able to take on much larger projects was the fact that I won the Wallonia-Brussels Federation call for projects

Alice Khol

Much like Yoann, the director Alice Khol has also had the good fortune to benefit from this much-vaunted grant. ‘What triggered me being able to take on much larger projects was the fact that I won the Wallonia-Brussels Federation call for projects. I saw that as an opportunity to practice directing: creating images, creating a narrative to music, etc. This grant has significantly changed the landscape in Belgium. But it is extremely rare to see such a budget for a music video,’ she clarifies. In addition to giving directors the opportunity of working in better conditions, to rent quality material and to pay their teams, the aid provided by the Wallonia-Brussels Federation also enables the offer of music videos in Belgium to become diversified. Thanks to this budget, Alice has in particular been able to produce a series of seven music videos for the artist Pierres. A large-scale work of unlimited creativity, which perfectly expresses the out-of-sync world of the Brussels artist. ‘Pierres had three EPs of demos. I thought to myself, that’s a lot of tracks (laughs). No problem: the duo decided to embark on the production of a mini-documentary which presents a day in the life of the artist in the style of Strip-Tease. ‘Pierres’ songs talk about the poetry of daily life, moments of the day and feelings in relation to quite simple things. I thought that he could have a complete day of his life set to the rhythm of songs, like an inverted musical comedy. I submitted the file, we had the commission and together we rewrote all the stages of the story. I wanted it to be a little bit off-the-wall, a bit funny and that it corresponds to Pierres’ world.’

Appointed as one of the members of the commission, Maxime confirms this idea: ‘The grant led to the emergence of types of music video which I hadn’t seen before. I am seeing the emergence of the viewpoints of authors which have been more worked on and polished (…) perhaps the fact of having been through the process of submitting an application, of having had to charm a commission, of having had to prepare more complex funding plans, pushes them to carry out more developed aesthetic research. They cannot settle for mere promises, they have to be convincing.’ This year, the music videos subsidised by the Wallonia-Brussels Federation were projected at the VKRS festival, the sole music video festival in French-Speaking Belgium. Held at the Théâtre des Riches Claires, each year the festival organises a national music video competition. ‘On average we receive 300 per year and we choose thirty or so,’ notes Maxime. VKRS is also a speed clipping competition: a challenge laid down to teams of video makers who receive a song selected at random written by a group which is at the festival and who have three days to produce a music video. ‘First of all, the festival allows these two milieus to encounter each other: the audiovisual and the musical world, which were not used to mixing together.’

Social networks, trends and adapting to new media

On December 2, 1983, the American television channel MTV shattered audience figures by broadcasting the well-known music video to Michael Jackson’s song ‘Thriller.’ A genuine short film which enabled the artist to promote his musical world whilst offering his audience an unforgettable audiovisual experience. Since then, the distribution channels have evolved, as have our consumption patterns: we no longer sit in front of the television to watch music videos on MTV – or on MCM, for that matter –, but on request on YouTube, Spotify, TikTok and Instagram.

On TikTok and Instagram, people don’t want to see images which are too clean, too produced. They want to see something real, or falsely real

Benoît Do Quang

This media evolution has obviously had a colossal impact on the ways music videos are thought through, and has led to the emergence of intermediate types of content. Alongside the music videos, ML has got into the habit of publishing audiovisual content on the social networks. Her thing? Instagram reels, these vertical videos by means of which she spotlights her creative work, her friends or her nocturnal bike rides through Brussels. ‘There is something I find very positive with the social networks, this potential to make this type of intermediate content. For my part, I love making Instagram reels about everyday life, filming things with my telephone to eventually use them as promotional tools, whilst recounting my way of life,’ explains the artist. In Benoît’s opinion, it is on the social networks that bricolage, the authentic, the DIY should be privileged. ‘On TikTok and Instagram, people don’t want to see images which are too clean, too produced. They want to see something real, or falsely real. But clearly, they want to have the feeling that you have placed your phone on the edge of your desk and you have filmed yourself playing,’ points out the director.

That being said, the presence of artists on the social networks is nothing without their music, nor the music videos which accompany it. ‘There are few channels which actually die. If you go back 60 years, there was radio, television, the press, and billposting. To that have been added masses of channels, but the standard media are still there. It’s the same thing in the music industry: the basis remains the piece of music. But to that is added the music video, which has been the first materialisation after the artist’s presence on the stage. Finally, there has been added the very orchestrated activity on the social networks,’ explains Hugues Rey, the director of the Havas advertising agency. And these music videos come in every variety: video lyrics, visualisers, short film or mini-clips a minute long, there is something for every taste. The key thing here is to offer content which is relevant, which can catch the gaze of the public. An expert in these matters, the American rapper Tyler, The Creator does this to perfection, in offering music videos which are shorter than usual. ‘He takes his song, he chops it up, he does a couplet and a chorus, he makes a really cool but very condensed music video. He has a very visual universe so he doesn’t want to forego it, but on the contrary he adapts to the ways people consume so he makes something shorter and more intense,’ notes Benoît.

Motion capture, 3D animation and artificial intelligence

A few years ago, Yoann Stehr and Alice Khol jointly produced the music video “Balrog” by the Antwerp rapper Shaka Shams. A daring clip, with something of the feel of a science-fiction film, and which spotlighted a very particular technique: motion capture. ‘It’s a suit with sensors on every joint, which enables the movements of an actor or actress to be picked up by 3D software so that eventually you have a character who is moving without having to resort to animation,’ explains Yoann. ‘It’s a technique which originated in Hollywood and which was still very costly 10 or 15 years ago, but which has become very accessible. We bought a suit for 1,000 Euros, and all of the software packages are easy to access and learn,’ he adds.

With Super.Tchip, Yoann draws ever deeper from the drawers of technology: in each of his productions, the director and his associate – such as Simon Breeveld and Diogo Heinen – integrate a multitude of tools such as collage or 3D animation. This year, when he was working together with Diogo on the music video “Cheesecake” for the instrumental group ECHT!, Yoann got to know a tool which was simultaneously surprising, marvellous and terrifying, and which bore the attractive name of artificial intelligence. The process? ‘We begin by gathering videos – in films, on the internet, etc. Into those we will integrate images in collage, very crudely. For this particular clip we integrated an image of a castle made of sweets. Next, we changed the calorimetry of the whole piece, we processed the image we had recuperated a little, without for all that paying attention to the aesthetics – we made something very primitive, just to give indications of volume and colour. We threw all of it into the artificial intelligence machine, we prompted ‘a town with a castle’; the machine did its work and it gave us something awesome with a kind of castle in the shape of a sweet. Then it’s all smoothed out, everything is reintegrated, and everything works.’ Despite several back-and-forths in order to achieve the desired outcome, the artificial intelligence allows a considerable amount of time to be saved, whilst offering remarkable creative possibilities. A tool which is becoming increasingly precise, and which is evolving at a crazy pace: ‘Even whilst producing this clip, the tools changed as our work developed (…) It’s going to be very impressive, everything we will have the possibility of doing with artificial intelligence.’ It just goes to show, used wisely, artificial intelligence can do miracles. And if you still have doubts, just watch the music video to ‘Cheesecake’ to convince yourself!

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

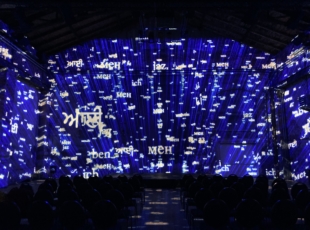

The Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles: a billion blue blistering harmonies