Morehshin Allahyari, the artist who reimagines history

Article author :

Whenever the influence of Western technological colonialism adulterates the traditional art of the Middle East and of North Africa, the artist Morehshin Allahyari appropriates digital tools and AI to re-figure myth and history. Her work weaves complex counter-narratives to dismantle and repair the Westernisation of this region’s visual culture.

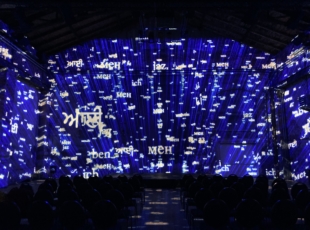

Morehshin Allahyari is an Iranian-Kurdish artist and educator based in New York and the San Francisco Bay Area. Making use of 3D simulations, videos, sculptures and digital fabrications, she reinvents myth and history. Her work ‘Moon-faced’, produced in 2022, will be exhibited in Namur at the KIKK Festival, October 24-27.

Activism and participation, the artistic vision of Morehshin Allahyari

Her art is steeped in history and activism and primarily focuses on the impact of colonial powers on the way we use technology, as well as its consequences on the global south. ‘I am inspired by my personal experiences to tell stories which express wider collective difficulties and realities,’ explains Morehshin. ‘I also believe in the power of communities and the creation of spaces. I like to see my work as projects on which other people may lean.’

To facilitate that, Morehshin bases her works on archives or research which she then makes available online or on reading tables during her exhibitions, so that others may appropriate them. ‘I see my work as an opportunity for other people to lean on in order to continue it, or to find inspiration in it.’

Queer identity and non-binarism in ancient Persian culture

A large part of Morehshin’s work is based on the search for historical material and the perception of History and new technologies, not in such a way that one of them makes reference to the past whilst the other is involved with the future, but to imagine a non-binary relationship between the two. ‘I observe the historical past and imagine what it could have been like, or the ways certain historical tales have been under-represented or forgotten,’ she explains.

Her project ‘Moon-faced’, created in 2022, was born from the desire to reimagine Persian and Iranian History. In ancient Persian literature, ماه طلعت (‘Moon-faced’ or ‘Visage lunaire’ in French) was an ungendered adjective which defined beauty in both men and women. Today, in contemporary Iran, this word has lost its ungendered characteristics and now only designates the beauty of women.

The paintings and photographs produced at the beginning of the Qajar dynasty reflected this non-binarism of gender expressed by the term ‘Moon-faced’. It was known, above all in its infancy in the nineteenth century, for its portraits representing people with non-binary and androgenous characteristics and queer couples. ‘We are talking about paintings representing women with monobrows or moustaches, men with slim waists and other typically female physical characteristics. In this period, this absence of a clear distinction between the male and the female was considered to be the apogee of beauty,’ points out Morehshin. ‘That shows us that it is easy to forget that the standards of beauty evolve and change to suit generations or countries. They have not always been those we see today.’

From the end of the eighteenth century up until the beginning of the twentieth century, this queer and non-binary culture changed and evolved towards something a great deal more gendered. Studies explain this transition primarily by the westernisation of Iran and the interest the kings of the period took in for Europe, being inspired by the traditions of the Old Continent to modernise the country.

With the democratisation of photography, it also became increasingly common for artists to use photographs as a model. Over time, the modernisation of Iran, the influence of the European tradition and the use of the photograph as a model brought to an end the queer representation of the genders which characterised these paintings.

Reimaging the queer portraits of Persian visual culture

For her project ‘Moon-faced’, Morehshin Allahyari trained an artificial intelligence to recreate queer and non-gendered portraits in the manner of the paintings of the early period of the Qajar dynasty to rediscover this history which had been lost over the years. At the time she embarked on her project, in 2022, there was very little material available on the subject which an artificial intelligence could be supplied with. Morehshin thus had to herself create a database from the archives and documents of the period.

‘It took time to create a database large enough for the programme to produce the images I was hoping for,’ admits Morehshin. ‘It was a complicated process. My work is to a great extent based on the effects of colonialism on the global south. AI is obviously a part of this system and it is biased. The majority of its databases come from these very specific chains belonging to the global north. It thus meant I had to create my own central library from which the programme could be supplied to circumvent the biases within the material available at the time.’

Through ‘Moon-faced’, Morehshin hopes to, first of all, reimagine the artworks which could have existed today if the traditions had not evolved in the way they did owing to western influence. Then, the project allows this strand of the history of Iran to be placed within a wider context and allows us to understand the immediate, snapshot aspect of the life we are experiencing. ‘Currently, the way we understand beauty is very gendered and it is easy to imagine that it has always been like that,’ explains Morehshin. ‘However, the norms, the laws and the ways of living we are familiar with and which to us seem to be the only ways of existing in the world do not at all correspond with the reality of a 100 or 200 years ago.’

‘Moon-faced’ is above all a speculative work, which raises the question ‘what may have been?’ and offers an invitation to open up to the multiplicity of realities. ‘History teaches us that, if society is such that it is at the present time, that is not to say that it has always been so and that it will always be so,’ assures the artist. ‘The truth is made of numerous layers and the choice of who we can be in this world is down to us.’

In the case of gender identity and standards of beauty, queerphobia and homophobia remain strong societal features in Iran. Yet, 200 years ago, the questions of gender and the ideals of beauty were more openly explored and less locked away. Today, the standards by which a man is considered attractive are more gendered, and everything which lies outside them are considered queer, which literally signifies ‘strange’ or ‘out of the ordinary’. It is for that reason that it is vital to understand historical contexts and to explore other possibilities of the true.

The work of Morehshin Allahyari can today be discovered in various exhibitions across the world. Certain of her works can be viewed at the Victoria & Albert Museum, in London, at the Contemporary Arts Institution at the Maine College of Art & Design, and at the Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, in Denmark.

Her project ‘Moon-faced‘ created in 2022, can be discovered in Namur at the KIKK Festival, October 24-27.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

The Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles: a billion blue blistering harmonies