Julie Henry, shattering the codes and degendering the digital

Article author :

IT engineer, ideas-person, blacksmith, beekeeper… Julie Henry has a life which is far from the run-of-the-mill. And is working on building a digital world in which women increasingly feel they belong.

She has faith in the digital future. And is forever encouraging young people to embrace STEM (sciences, technologies, engineering and mathematics) educational pathways. Pushing them to imagine the professions of the future. Insisting on their social impact. And strongly encouraging girls to be part of the adventure.

To pave the way for them, Julie Henry is working on an educational programme aiming to make teaching materials and education gender-neutral. ‘It involves showing teachers their gender biases. For example, the fact that they give boys more time to express themselves in the classroom. And as a result of that, the girls get used to talking less, to interacting less.’ And, in the end, get accustomed to sidelining themselves. Enabling girls to have more self-confidence is one of the keys to their inclusion in STEM courses.

This project is part-and-parcel of her job as STEAM project manager – with an A for art. Once she had obtained her doctorate in computer science, the UNamur Rector, Annick Castiaux, offered Julie Henry a two-year contract to develop STEAM aspects internally and with external partners. It was in this way that the STEAMULI platform, bringing together all of the Namur STEAM actors, was created.

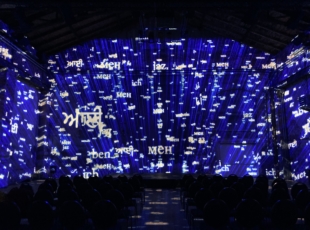

‘When we talk about STEAM, we are talking about a pedagogical project-based approach whose goal is to develop creativity. That requires establishing specific creative and artistic pedagogical activities, over a certain period of time. Recently, we created a certificate to train teachers in this new pedagogy which is clearly breaking down the barriers in the sciences.’ And making them easier for children to like.

Never the right time to have a child

Now a public figure in the battle to lead more young people, and in particular girls, to take up science courses, Julie Henry struggled during the first part of her professional life: multiple difficulties in getting funding for projects, part-time appointments, contracts lasting no longer than a few months. ‘I had to prove myself each time. I worked hard without considering the hours it took to try and get to a point where I could say to myself that it was worth staying.’

For a long time she privileged her researcher career, with heavy obligations to make her research results more widely known by means of numerous publications and at colloquiums abroad. And she kept putting off motherhood. ‘Since I was starting doctorates without ever managing to complete them [Editor’s note: she was finally awarded her doctorate at the end of the third], there was this pressure to tell myself I had to get through a doctoral degree before having a child.’

‘No one ever tells you in so many words that maternity is a problem, but you feel that it will interrupt the rhythm of your research. A gap of 3 or 6 months in your scientific CV, without a publication, in other words, is dreadful. What’s more, when you return to the lab, you have to bust a gut twice as much, because things have changed a lot in your absence.’

In the end, it was during her fortieth year that Julie Henry gave birth to a little boy. ‘I finished writing my thesis with a huge belly. When it came to my private defence, I was eight months pregnant. During my maternity leave, I had to spend a month rewriting an entire chapter of my thesis. And come back to the university to defend it in public.’

The Big C makes an appearance

Several months later, in the spring of 2023, scarcely having had the time to enjoy her baby boy, Julie Henry was struck by grim news. ‘On March 28, I read the result of my biopsy: invasive stage 3 cancer. On April 6, I officially became a triplet. On April 11, I had my portacath fitted. On April 12, the first chemo. … In January, the doctor had said to me, ‘you are forty years old, it cannot be cancer’, she writes on X.

Le 28 mars, je lisais le résultat de ma biopsie : cancer invasif stade 3.

— Julie Henry (@HenryJulie) April 13, 2023

Le 6 avril, je devenais officiellement une #triplette.

Le 11 avril, on me posait mon pac.

Le 12 avril, première chimio.

…

En janvier, le médecin m'a dit "vous avez 40 ans, ça ne peut pas être un cancer". pic.twitter.com/spA0vj4XxF

‘I forced myself to work up until the beginning of May and I went back to work at the beginning of July on quarter-time, because, even though I was in the middle of my chemo, I was going to be saddled with a CV problem: every time I would have an interview for a researcher job in the future, I would be asked to explain this period without research. And if I let slip that I had cancer, it is highly likely that they will find some other reason not to hire me.’ The unfair realities of the world of work.

Triple-negative breast cancer accounts for 15% to 20% of all breast cancers. ‘Why me? I never asked myself this question. On the contrary, why wouldn’t it be me, why would the others deserve it more than I do? If, out of 8 women, 1 systematically has to have cancer, I prefer it to be me rather than see others suffer. And there is no need to feel anguish at seeing me be ill. There are people who are suffering a lot more than I am all around us.’

A love story with Africa

These words constitute the message she wrote last December as a foreword to her public request for financial support to help Upendo Tu. This non-profit association provides aid for refugee groups in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo. ‘Each year, we organise activities to raise money in order to feed the children who live there. But there are so many of them that it is almost a mission impossible,’ she regrets.

This love of Africa has made its way as far as her musical practice. Julie Henry plays in Djolé (with the name taken from a Guinean rhythm), a group of classical African percussion instruments, along with her husband. The djembe and the dundun (large tambours turned into drums and beaten with sticks) make their hyperactive rhythms heard in their part of Belgium.

Popularising computer science and reducing the digital divide

For once, the symbolic coffee machine was the starting point for a wonderful collaboration. It was owing to bumping into each other there that Julie Henry, Fanny Boraita and Benoît Vanderose, two colleagues at the UNamur computer science faculty, decided to create digifactory. ‘We were all interested in the issues of digital inclusion and access to the digital world for the greatest number of people. But also in the creation of innovative tools enabling the general public to learn the digital, to be able to get to grips with what the much-talked about black box is, but without it being daunting, or too theoretical or too superficial.’

Through the non-profit association, the trio responds to small-scale appeals for one-off projects, such as those issued by the Digital Belgium Skills Fund or the King Baudouin Foundation. A book has been published, and a MOOC has been created with digital caregivers in mind. ‘At the moment, we are consultants concerning the didactic aspects for CodeNPlay in Brussels, an association which takes computer code into the schools and arranges training courses specifically for children. At this stage, we will not develop digifactory further. But at the end of my contract at the UNamur, it may well serve as an escape route.’

The blacksmith and her robot

Whilst we are on the subject of escape routes, Julie Henry has devised several for herself. A beekeeper, a teacher of apiculture, but also a blacksmith. ‘I could have turned it into my profession. And brought gender issues to it as well. As a matter of fact, when I was doing my training course, I was told that I didn’t have the necessary strength to do this work. But I discovered that it wasn’t necessarily true. Yes, I learned to forge by hand, with a hammer and using an anvil; but in a work context, all the heavy-duty tasks are, on the other hand, carried out by a robot. It’s the robot which carries the items and you simply have to learn how to use it. In the end, all it remained for me to do was know how to weld, cut and assemble; my strength was no longer a problem. That’s how in my free time I have forged enormous metal gates inside horse stalls.’ The sky is the limit.

Hier, j'ai voulu dépasser les limites que me fixe la chimiothérapie. J'ai donné une conférence le matin, enruché un essaim l'après-midi et donné un concert de djembé le soir #djolé

— Julie Henry (@HenryJulie) April 29, 2023

"Ne t'arrête pas quand t'as mal mais plutôt quand t'as tout donné" pic.twitter.com/AeXDIAo4S7

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.