Jean-François Rees, towards the scientific research of the future

Article author :

Jean-François Rees has for several years now been combining the arts, sciences and creativity in his teaching of animal biology at university. This explosive blend will also serve as an ingredient in his next research project, based on the graphic printing of fungi and bacteria.

Born neither into a family of artists, nor into a family of scientists, nothing in his background suggested he would end up mixing the two disciplines. Yet it has now been several years that he has been joining forces with artists in order to find alternative ways of talking about the sciences to the general public. A lecturer at the UCLouvain, Jean-François Rees teaches animal biology, creativity and scientific procedures.

Organs and non-vertebrates of the future

Together with the artist Isabelle Dumont, he created ‘Fossils & Fictions. After us the jellyfish?,’ the exhibition held at the Musée L up until mid-May 2023. Its goal? To consider the forms that living things might take over the next millions of years. In it, visual arts students at the ART2 school (Mons) offered several surprising chimaeras, whilst students from Prof. Rees’ Bachelor’s in Biology first-year class displayed plates revealing the organs of the future they had imagined.

‘Creativity is vital in my eyes. That is why I include it in all my teaching, in the work the students have to carry out, the appraisals of it. And I do so from the very first year of the degree. Once I have explained the different systems of the human body to them, I tell my students that we will go further still. You have to understand that our body was designed 200,000 years ago. It has evolved little since that time, but human beings have completely transformed their environment, which has created new needs: I ask the students to imagine a new organ which would enable one of these needs to be met. Each year, 150 new organs are in this way suggested to me! These fledgling scientists of the future appreciate being able to let their imaginations run wild, to go off the beaten path.’

‘In the 2nd year of Biology and Bioengineering, I give a course on the non-vertebrates. Once they have familiarised themselves with all the branches of animal evolution, I ask the students to create a non-vertebrate of the future belonging to such or such a group (a mollusc, for example), one which is endowed with characteristics that are a bit crazy: they move around by means of rolling, use hydraulic energy, a part of their DNA comes from a plant, etc. They have to describe all of the systems, like we do for current living organisms, provide diagrams, cross-sections. In short, to demonstrate through a rigorous scientific process that their animal makes sense and is viable. They produce such amazing things.’

A few years ago, the artist Pierre-Yves Renkin sculpted around ten or so of these curious creatures in 3D. Ranging from 80cm to 1m in height, they were part of an itinerant exhibition, ‘The animals of the future.’

Scientific culture

When at university, Jean-François Rees followed the typical pathway of a good student. Just when he had completed his thesis in biology, the UCLouvain was concerned about the recruitment of students into the sciences. Less and less were opting for them. ‘I had just devised an activity for young people who, taking part in the “Jeunesses scientifiques” events (an organisation which aims to raise interest in the sciences amongst youth), had won this European competition. In the wake of this success, the Dean at the time sought me out to ask if I would develop something to boost young people’s curiosity in the sciences. It is in this way that Science Infuse was born, which was later to become “The Springtime of the Sciences,” the annual meeting of sciences and technologies in Wallonia and Brussels.’

‘I love communicating science. In my opinion, if science isn’t being communicated, then there is not a lot of point in doing it.’ This opinion led to him being recognised within the Louvain-la-Neuve university as somebody interested in scientific culture. ‘I therefore joined the Council for Culture. And I noticed – with some surprise and bitterness – that, for many people, unlike the arts, the sciences weren’t part of culture! And that it was a matter for debate. For my part, I have for twenty years been arguing that science is an important aspect of culture. In fact, science is a process which is handed down from generation to generation, like language, ideas, philosophy, the arts.’

Jean-François Rees then became a culture advisor to the Rector at the UCLouvain. ‘Whilst I was already keen on music, my new role led me to become interested in the graphic and visual arts. I was immersed in artistic cultures I didn’t know very well. We discussed the arts, arts in the culture, I worked with artists in residence. All of that gave me immense pleasure.’

Interpreting graphic design in scientific terms

Influenced by his artistic encounters, Jean-François Rees has himself set the wheels in motion of an artistic-scientific project, starting in September 2023. He has in fact just been granted a sabbatical year which will allow him return to the nuts and bolts of a graphic design project involving micro-organisms he had embarked on a few years ago.

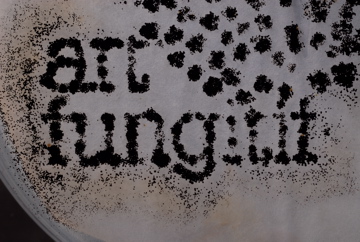

‘Within the scope of my teaching, I discovered that some people had had the great idea of taking an old HP printer, removing the ink from the ink reservoir and replacing it with cells in suspension, and then printing these cells. They thus succeeded in creating distinctive patterns. At that time, there was an incredible collection of fungi on the floor below mine, and I wondered if I could come up with a terrific project, with the idea of developing graphic arts. So, having placed fungi spores in suspension in the ink reservoir of a simple 2D printer, they are then printed onto paper, which is then placed in growth conditions so that the pattern can develop. We had fun with it, but it all ended rather sadly, because my colleague died after a few months.’

Having been placed on standby for several years, the project will thus be given new life. ‘I would like to co-print different species of fungi, bacteria, and to see if their ecological relationships (collaboration, cooperation, parasitism, etc.) might be revealed via distinctive graphic shapes. In other words, to develop a very simple graphic method qualifying the relationships between living species.’

‘What I love about the arts is the freedom. Occasionally, in the sciences, I feel a little hemmed in. Yet I adore the sciences. But it’s marvellous to have this freedom, to take the path less travelled, to add a little humour. I like this disruptive, creative aspect, finding unexplored pathways which have been in front of us for a long time but down which nobody has ventured. And inventing a subject.’ Another project Prof. Rees will be getting to grips with in the coming months focuses on the 3D printing of animal tissues. And the objective in this case is a reduction in the use of laboratory animals.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

The Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles: a billion blue blistering harmonies