When influence marketing inundates culture

Article author :

Are you aware that influence marketing may guide your next reading choices or insinuate itself within the most iconic museums and festivals? But what does it consist of in concrete terms, how is it used in the culture domain and with what impact?

‘Influence marketing’: a conjunction of two words which seems both so crystal clear and abstract. What are we talking about when, when we come across this concept in a conference, an article or a post on social networks? According to the illustrated Encyclopaedia of marketing (in French), it involves ‘the whole of the practices aiming to use the recommendation potential of influencers and other content creators for commercial or marketing purposes.’

The practice of engaging with opinion leaders or people with expertise/legitimacy in a specific domain is not new. However, it has metamorphosed in regard to the emergence of social networks. Gradually, this marketing trend has also gone digital. The Culture Régie (a dedicated site specialised in marketing) explains: ‘throughout its history, influence marketing has constantly evolved to adapt to changes in consumer habits and to technological advances. It encompasses a wide range of platforms and types of influencers, offering brands numerous opportunities to connect with their target groups in authentic and meaningful ways.’ One of the first examples of influence marketing in the digital era dates back to the beginning of the 2000s, a period when blogs represented the Holy Grail of every ‘cool’ person on the web. Heather Armstrong, a highly followed blogger, went into partnership with the Ford automobile brand. The outcome? Her ‘Dooce’ blog acquired a massive audience.

‘Marketing’ + ‘Culture’: since when and why has this match been considered feasible?

Today, influence marketing is no longer exclusively used to promote car, clothing, make-up or food brands. It is also gaining traction in the culture domain.

Delphine Jenart, a lecturer in cultural communication practices at the UCL Fucam and digital culture mediation at the IHECS, explains: ‘The figure of the culture critic is very familiar to us. A journalist such as Hugues Dayez (RTBF) remains the cinema prescriber for a large proportion of the generation of 40–60-year-olds in French-speaking Belgium. What has brought about the shift from the culture critic on primetime channels to the cultural influencer who for the younger generations perhaps now has more credibility when it comes to choosing a book to read, a film to go and see at the cinema, a site to visit?’

The expert responds to this question and explains it by the fact that the media are evolving. ‘Our relationship with the media is changing; we no longer get our information or make our cultural choices in the same way. The influencer is in a way a “symptom” of our networked medias; it therefore makes sense to see influence marketing entering cultural institutions.’The notions of ‘marketing’ and ‘culture’ would appear to be antithetical in Europe’s cultural institutions, specifies the KIKK coordinator for wake! by Digital Wallonia. Yet, she develops her argument: ‘it is an alloy with which people are much more comfortable across the Atlantic, but that is in the process of changing. The digital transformation we have been living through for a good twenty years or so has progressively encouraged this convergence, in particular through the urgent need to diversify the cultural sector’s sources of funding, as well as its audiences, with the objective being rejuvenation.’

#BookTok: the hashtag which is wreaking havoc on the world of literary publishing

Thus, more and more influencers are having a real impact on the cultural choices of the young generation. That is for example the case of François Coune. A Belgian queer literary critic, he is followed in particular for his literary recommendations on his Instagram account @livraisondemots.

His fame has led him to organise events which carry weight in the publishing world. He oversees the bloggers’ Grand Prix (awarded by plugged-in readers). He also published a book in 2023 (Et si on livrait des mots (And what if we delivered words)). On his Instagram account, he hosts authors to talk about their works. He guests on news programmes to offer reading recommendations. Booksellers well known to the general public (such as Club) have offered him numerous partnerships. Want to find out more about his story and activities? Head for the Compose podcast.

François Coune is what is known as a Bookstagramer. Come again? Originally, the phenomenon took root with the arrival of YouTube. ‘The BookTubers are very keen video makers on the subject of reading, who talk about literature on YouTube,’ points out France Info.

The concept has taken various forms on other social networks, in following the same idea. It is therefore no great surprise that it has arrived on TikTok, with the #BookTok (which as a whole has gathered hundreds of billions of views). Thanks to its use, an international community has been created. The users publish Reels on their preferred reading, recommending books to those who follow them, also sharing critiques, lists and reading tips.

@lybooks C’est quoi le livre que tu recommande absoluement ?? #booktok #book #books #booktokfrance #livre #fyp #livresaddict ♬ son original – Lybook

The impact of #BookTok is immense, in particular amongst young people aged between 16 and 25 years. This has been made clear by an inquiry carried out by the British trade organisation of the Publishers Association in 2022: of the 2,000 surveyed, 59% said that the TikTok literary network has helped them ‘discover a passion for reading’.

An opinion shared by Louis Wiart, a communications lecturer at the ULB. He shares several remarkable figures contained within a study published by the National Book Centre in France (2023): ‘44% of the under-25s say that the recommendations of influencers on the social networks may guide them and lead them to buying a book. For the age bracket above (25-34 years), 37% of them say that they may possibly buy a book following this recommendation […] That demonstrates that the social networks for the under-35s are genuinely a lever to steer reading and purchasing practices. That is one of the conclusions of this study.’ And to no great surprise, when you climb these age brackets, the impact of online influence marketing diminishes and affects solely 4% of the sixty-five and over sector, once again according to this study.

Being an ‘ordinary expert’: the recipe which makes online influence marketing work?

Louis Wiart has published an academic research article, ‘Les livres sous influence’ (Books Under the Influence); in it he in particular refers to the notion of ordinary expertise. The lecturer explains: ‘in comparison with the traditional literary critic, what constitutes the value added and the power of the influencers, is not especially being literature specialists/experts or being great connoisseurs […] it is rather their ordinary character which will play in their favour, the fact of being people who are perceived as being authentic, and therefore as ordinary. […] That, in short, creates a close relationship with the audience which watches these videos or consults these posts on the social networks. That is also what the publishing houses are looking for. If they are making use of the mediation of an influencer to ensure the visibility of their books, it is because they gain something different in comparison with traditional advertising: this sense of authenticity.’

In France, up to 20% of the marketing budget of certain books is earmarked for influence marketing, as this article in Le Monde points out.

According to the lecturer, it is this notion of ‘ordinary expertise’ which would explain why publishing houses opt for influencers: ‘that allows them to disseminate a commercial message without it appearing to be overtly commercial […] the content of an ordinary internet user but which, in reality, conveys a commercial message. There will thus be a softening of advertising discourse and that will increase its effectiveness.’

As Delphine Jenart points out, influence marketing is a regulated domain, from the moment it shares the codes of advertising: ‘there are bodies such as the CSA which provide support for and guide the influencers, or the ethical advertising jury which plays a role in regulating advertising in Belgium by ensuring a balance between freedom of commercial expression and protecting consumers against potential abuses.’ Because, whilst online influence marketing is prospering in the world of literary publishing, it is not restricted to this cultural domain, quite the contrary!

Influence marketing also exhibits in your favourite museums

The Felicien Rops Museum in Namur has employed the services of the YouTuber Benjamin Brillaud. His history popularisation channel ‘Nota Bene’ has 2.5 million subscribers. The cultural institution wished to increase its visibility, reinvent itself and broaden its public. In an RTBF article, Véronique Carpiaux, the museum’s curator, notes that ‘Nota Bene’ addresses the whole of the French-speaking areas worldwide: ‘some people expressed reluctance when we decided to work with YouTubers. Because they are often lumped together with influencers who place brands and whose approach is purely commercial. But it has to be understood that there are large numbers of people who share cultural historical content which has been academically verified.’

For her part, Delphine Jenart considers this approach appropriate: ‘that he has made use of Rops’ work to open it up to a segment of the population which might not have spontaneously visited the Namur museum is a positive thing, it seems to me. It matches the very concept of popularising science. Encouraging people to “give something a try”.’ She then emphasises that ‘whilst cultural marketing tends to be sales-oriented, cultural communication pursues educational and informational goals to lead the public to culture for emancipatory purposes; it’s not the same thing.’

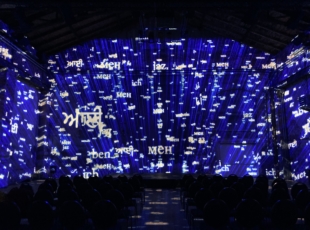

In other respects, she points out that culture has not stood by helplessly when dealing with this wave of influence marketing. She lists several striking examples. Since 2016, the Louvre in Paris has been offering invitations to YouTubers (including Nota Bene). The same is true of the well-known Tate Modern and the Tate Gallery. Popular music festivals (such as Tomorrowland) also involve influencers to grab the attention of their audiences.

@thecuriouspixie Everyday is a school day especially when you spend it @tate modern #London #LondonArtGallery #PlacesToVisit #ThingsToDoInLondon ♬ Curiosity – Danilo Stankovic

‘It is vital to stress the issue of education to the media so that influence marketing becomes a genuine qualitative lever for cultural institutions. The higher the level of media literacy and the critical perspective it offers, the better the lived experience will be,’ concludes the expert.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

NUMIX LAB 2024: creating bonds and building the future of digital creativity