Hovertone: the (digital) art of mediation!

Article author :

Interactive installation, mapping, touch screens, etc. Cultural institutions and scientific culture centres are increasingly accessing digital mediation tools. And that is precisely what the Hovertone studio specialises in. Established in Mons, it has been imagining and designing digital experiences for different audiences since 2015. Nicolas d’Alessandro, the studio’s co-founder and artistic director, shares his vision of interactive design and reveals a few of the secrets to involving audiences and facilitating content delivery.

‘We love investigating the sites where people happen to be, which they are passing through. The idea that they might stumble upon, almost by accident, some cultural content, some information they weren’t aware of, is at the centre of our process,’ Nicolas d’Alessandro explains at the beginning of our interview with him. Hardly surprising then, to see the diversity of Hovertone’s play areas: museums (Musée de l’Homme, Beaux Arts de Mons, Musée du Doudou, Bozar, etc.), centres of scientific knowledge (Quai des savoirs, Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie, SPARKOH!, etc.) or public spaces (Parliament of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation), etc. In concrete terms, what types of immersive experience are designed for these spaces? Very early on, in the 2010s, the team – which calls itself a ‘creative agency which has swallowed a tech startup’ – fully absorbed the technology of magic boards and interactive video walls allowing multiple uses. An illustration is provided by The Song of the Machines (2017) installed at the PASS (Science Adventure Park, in Belgium): this scenography, presented on a former mining site, is composed of enormous wooden panels on which visitors can activate seven imaginary machines and a soundscape. ‘It’s a technology which involves the viewers. The effect is guaranteed: every time, I see the look of wonder on the audience’s faces’, comments Nicolas d’Alessandro. This principle of an interactive surface also shapes other mediation initiatives imagined and designed by the studio: Traces (2021, KIKK Festival of Namur), Links(2020, Mons) or From the origins of the Universe to the layers of the atmosphere (2020, EuroSpace Center), in which a wall 11 metres in length invites the public to meander across the complex processes of the creation of the universe.

Sensory experiences

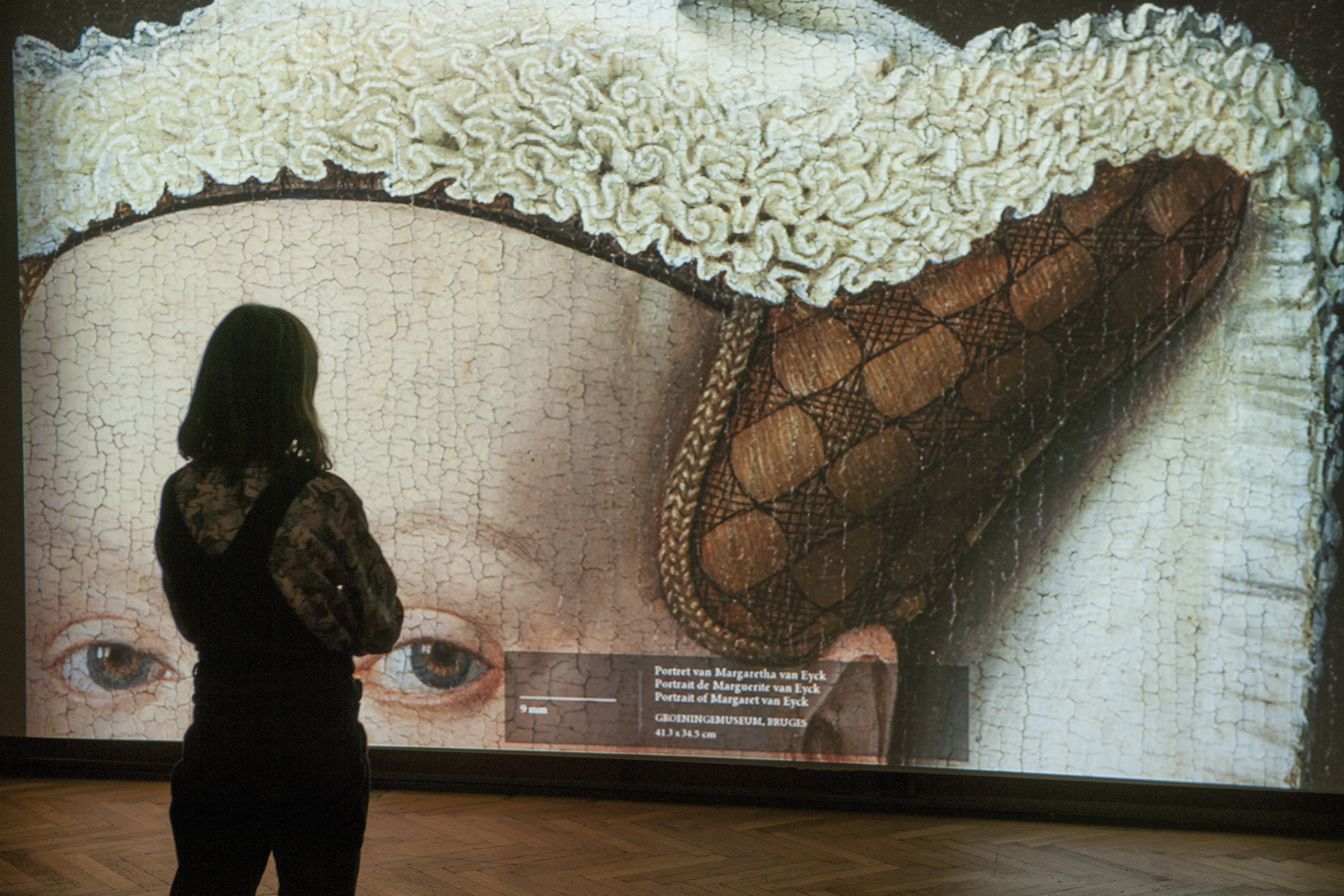

Mapping is also a tool the studio privileges to explore the concept of sensoriality. For example, how to place yourself in the skin of an artist and discover their work by other means? The interactive experience Shooting by Niki (2018), presented as part of the exhibition dedicated to Niki de Saint Phalle at the BAM (Beaux-Arts Mons), allowed visitors to relive, from the artist’s viewpoint, her action paintings (rifle shooting at pockets of paint attached to her works). The visitors could thereby experience for themselves the whole process of the ritual: picking up a rifle, loading it, aiming, firing and seeing the paint explode across the video-projected canvas. The Facing van Eyck : The Miracle of Detail (2020) experience, presented at the Bozar, goes further still and immerses audiences in hitherto unseen ways in the paintings of the fifteenth-century Flemish pioneer of painting, well known for the minutiae of his brushstrokes. Details scarcely visible to the naked eye take on another dimension thanks to high-definition scans of his works. Nicolas d’Alessandro explains: ‘we worked with the Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique (KIK-IRPA), which had produced scans, radiographs and reflex prints of all of the canvases painted by Van Eyck, and was trying to find attractive ways to present them to the general public. Hovertone’s idea was thus to invite the audiences to immerse themselves in all the details of a canvas and gain access to some of the painter’s secrets, thanks to the movements of the body. They were as close as it is possible to get to the artist’s brushstrokes and dynamism.’

Several keys to digital mediation success

Whatever the technology used might be, these installations have one point in common: stimulating the participation of the public and triggering personal and collective forms of appropriation. ‘Grabbing people’s attention is vital to transmitting information, or the key concepts of cultural or scientific projects,’ confides Nicolas d’Alessandro. An important key in the mediation process which often takes the form of the gamification of the apparatus. ‘McLuhan said that “the medium is the message”. It means that our role is to imagine ways of getting messages across, tools which are true to the content and which are in harmony with the typology of the audiences concerned.’ And to achieve that, it is necessary to be able to understand the ideas underpinning a project, to bring out its substance, editorialise it, design the experience. Hovertone has therefore worked in this manner with SPARKOH! on an interactive installation intended for children, based on the periodic table of the elements (The Odyssey of the elements, 2019). Hovertone’s artistic director continues: ‘our primary intention was to offer a fun, not off-putting, learning experience based on chemistry. We transformed the floor of an exhibition hall into an immense touch screen. The children were invited to walk on the shapes and in doing so liberated atoms which filled Mendeleev’s periodic table, which was projected onto the wall, accompanied by a trail of sparks.’ The children could race against the clock, play on their own or as part of a team. ‘The more technologies and immersivity there are in their homes, the more the general public will look for out-of-the-ordinary experiences when they leave them. We thus need to write narratives and think through quality experiences in public spaces.’

Despite this trend for digital tools, Nicolas d’Alessandro has no hesitation in pleading for a form of sobriety. ‘The digital is one form of know-how amongst others, and sometimes you have to get to a point where you choose not to use it. It’s the coherence of the project which counts and the synergy of these apparatuses with the mediation personnel.’ A form of deontology especially important given that cultural institutions and scientific culture centres are often keen on getting their hands on the keys to decode ‘tech’. ‘The museums, having today taken the path of digitalisation, need to provide themselves with effective and reliable frames of reference to properly oversee their next infrastructure investments. There is a crying need for support provision. To decrypt, to demystify the terms immersive, XR, AI, and to understand all the issues coming down the line. They mustn’t let themselves be blinded by technological trends. For example, on the question of environmental impact, we try to adjust our responses to the needs of the clients: can the equipment be used for other projects? How can the decisions made today still be relevant in the next five years.’ Far-reaching (and essential) questions in a perpetually moving world… which mediation allows us to grasp.

Nicolas d’Alessandro’s DONUT interview:

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

The Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles: a billion blue blistering harmonies