fleuryfontaine: thinking State-sanctioned violence by means of architecture

Article author :

fleuryfontaine employs architecture and digital technologies to explore several subjects of major concern to society: police violence, the impact of urbanisation on our bodies, loneliness and isolation… Through their most recent installations and 3D videos Antoine Fontaine and Galdric Fleury explicitly address the theme of State-sponsored violence. A zoom-in on a hybrid artistic corpus, midway between documentary and fiction.

The theme of State-sanctioned violence

At the beginning of the interview, Antoine Fontaine and Galdric Fleury – both graduates of the École d’Architecture de Paris Malaquais (2008), the École d’Arts de Paris-Cergy (2014) and Fresnoy (2020) – are keen to clarify their position: there is no question of labelling them ‘militant artists.’ Galdric Fleury explains: ‘We do not consider ourselves activists, but we do wish to bring things to light and take part in the debate by other means.’ All precautions having been taken, it has to be acknowledged that some of the subjects they handle are particularly complex. In 2020, the duo presented PAX and CONTRAINDRE, two works devoted to the subject of police violence. ‘In 2016, the social context in France was electric, with demonstrations against the Labour Law. Then in 2018, there were the yellow vests protests. From that moment, the media and political debate on the monopoly on violence skyrocketed. We wanted to try to bring a plus-value to the public debate in our particular way,’ explains Galdric Fleury.

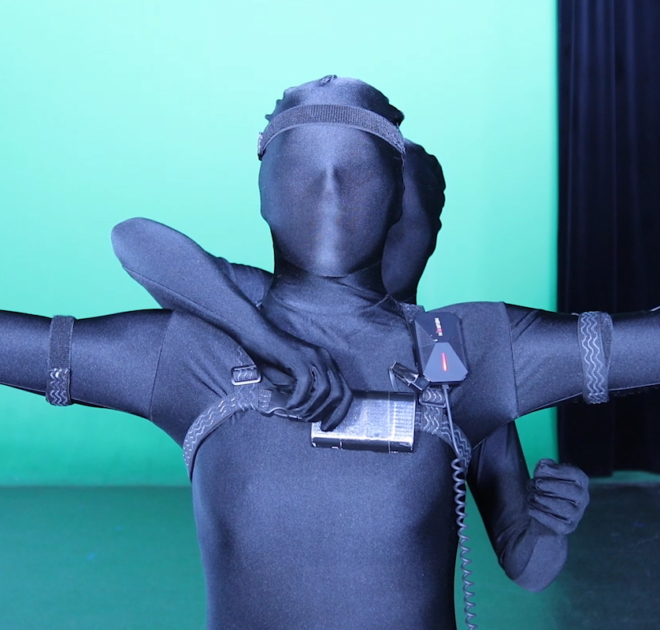

In concrete terms, PAX is an installation consisting of several video screens. On each screen there appears a section of a mutilated body (cuts, bruises, scars, etc.). These injuries are found on people who have been in clashes with the police in France. ‘The mutilated body appears progressively on the screens. In this way, we implicitly show the actions of the forces of law and order and the mutilations they engender. This questions the mechanisms of maintaining pressure on a population,’ specifies Antoine Fontaine. CONTRAINDRE continues this reflection in interrogating by means of a film (best international film, Ann Arbor Film Festival 2022 / Prix France Télévisions, Champs-Élysées Film Festival, 2021), how the space of a city can come to coerce the bodies of the citizens. ‘Military concepts have taken root in the language. This lexicon of “theatre of operations” tipped the city over into the idea of a battlefield. Remember that the media spoke about certain neighbourhoods as “lawless no-go areas, which had to be reclaimed”,’ continues Antoine Fontaine.

A documentary and sensitive approach

In these two keynote works from the fleuryfontaine corpus, the concept remains identical: raising awareness of the mechanisms of State violence. ‘It is also for that reason that we didn’t wish to show police officers in our videos… The most important thing is to identify the general mechanism,’ emphasises Antoine Fontaine. The writing of bodies undergoing suffering is thus inspired by real cases. This documentary approach is sourced in three ways: ‘the first is via Twitter or YouTube and is based on real images. The second source consists of gathering information from the press and the journalistic work which is produced. The third source consists of analysing the academic literature (urban planning, philosophy, sociology). The idea is to understand the subject we are dealing with as best we can. To construct an overview and to treat it in a way which is not a factual reconstruction,’ explains Galdric Fleury. This approach therefore nuances the often-existing border between documentary and fiction: here the objective is to come face to face with the real whilst offering a sensitive perspective.

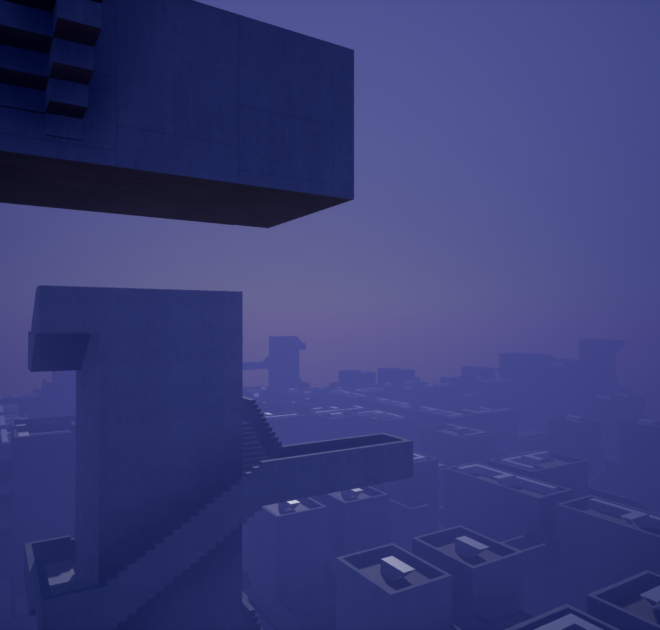

‘Given the subjects tackled, we cannot produce a superficial treatment of them. We are talking about serious subjects and mastering the narrative is essential. We are greatly concerned with never distorting the emotions of the people who are victims of violence, which is why we try to be accurate and relevant,’ continues the artist. We find this same in-depth work in ANGE, a film on the Hikikomori phenomenon, a term designating young adults and teenagers who choose to never leave their bedrooms or their apartments for months, sometimes even years, on end. ‘We raise questions about what is solitude, isolation. It is a subject we are sensitive to,’ points out Antoine Fontaine. This work recounts the story of Ael (‘Angel’ in Gaelic), who has shut himself away in a shed in the garden of the family home for 13 years, somewhere in the south of France. ‘We have had discussions with him over the internet. We used the medium of video gaming to attempt to recreate the world of thishikikomori. To engage in conversation with Ael, we created digital environments in which he lives. His bedroom, the objects found within it, the parental home, his neighbourhood, this film unveils the fragmented portrait of a man who has retreated from the world,’ the artists further explain.

The video game, a privileged medium

Video gaming features in several of their works. ‘First of all, for procedural reasons. We started by taking in hand the technologies of video games and software such as Unity 3D and Unreal Engine,’ explains Galdric Fleury. But also because video gaming ‘enabled interactivity and experimenting another space. That changes the way you see a work, in particular in comparison to a film already edited.’ YOU CAN’T STAY UP ON THE ROOF FOREVER (2016) and LES ÉLÉMENTS TOMBENT DU CIEL (2018) (Editor’s note: a work about staircases and paving stones) are two games conceived as walking simulators in which viewers can move around endlessly and in no matter which direction, in dispassionate environments, symbols of modernity. ‘At times, we have imagined documented works as performances. We “played” these video games in front of an audience. That was the case with the work LES ÉLÉMENTS TOMBENT DU CIEL, which we performed as part of a soirée held at La Villette and organised by Virtual Dream Center.’

Contributing to the public debate in other ways

Antoine Fontaine and Galdric Fleury have also explored other means of producing information and contributing to the public debate. In 2020, their work CONTRAINDRE led them to get in touch with the Forensic Architecture association, and then with its French counterpart, Index Investigation, which looks into matters of public interest with the aid of digital technologies and in particular 3D reconstructions. ‘Just as there is a legal, forensic, medicine, there is also a legal architecture, which analyses complex elements in space,’ explains Galdric Fleury. Antoine Fontaine concludes: ‘we stayed for two years at the Index, contributing to the reconstruction of several videos, like that of the violence committed against Adnane Nassih, the victim of a non-lethal weapon shooting. This work is above all informative and journalistic. It’s another means of contributing to a public debate. This time spent at the NGO has also fed into other practices. CONTRAINDRE led us to the Index. The Index led us to a new project which has as its starting point the Adnane Nassih affair. We move on from this investigation to make a short film which will be released in a couple of months.’ This new project will thus extend the reflection on State-sponsored violence in the continuity of an already extremely rich work focusing on architecture.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.