Chloé Desmoineaux, a technofeminist to the tips of her gamepad

Article author :

Having fallen into video gaming when she was a child, Chloé Desmoineaux is exploring alternatives to the prescribed interaction between screen, gamepad and body. Performances, repurposing canonical video games, installations where gaming is considered from a group perspective, the digital artist is deeply concerned with the position assigned to women and minoritised people in this still very testosteroned industry.

‘In the same way as certain literature and cinema classics, video games have always been part of my cultural frame of reference, with occasional time-out periods during which I played less,’ Chloé Desmoineaux tells us. ‘But taking an experimental, artistic or even political approach to video gaming was something I discovered later, when I was studying.’ After completing her lycée (our secondary education system), she, first of all, went to study at the Bourges École Nationale Supérieure d’Art, and then obtained a National Superior Diploma in the Plastic Arts at Aix-en-Provence. It was there that her notion of video gaming mutated. ‘I came across several teachers who progressively deconstructed my take on the media and video gaming. In particular a media theory course given by Nathalie Magnan.’ A cyberfeminism pioneer, Nathalie Magnan is a French media theoretician and activist, a women’s rights militant and director.

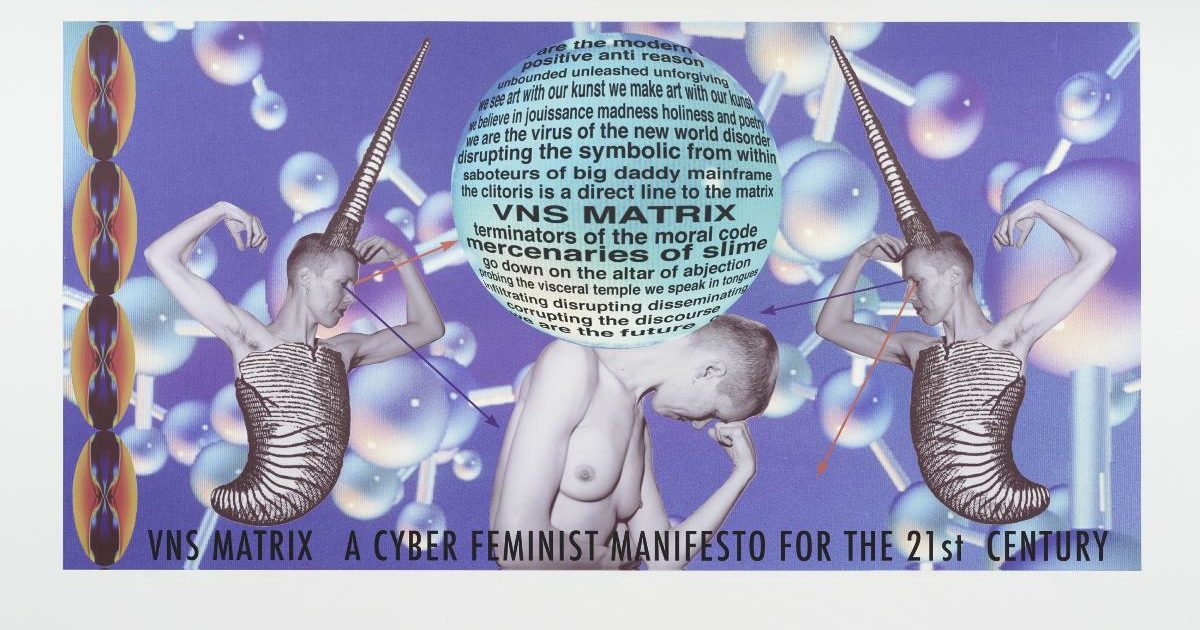

If, as is the case for us, cyberfeminism is not clearly defined in your vocabulary, we will provide you with a little context. The term ‘cyberfeminism’ was used for the first time by an Australian female artists collective called VNS Matrix. In 1991, its founders published A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century. The manifesto attracted a lot of attention, not for its prompting of direct action, but because with its outrageous and symbolically charged language it affirmed the existence, the position, the anger and the power of women in technology-related industries. And all of that, need we be reminded, when the internet was still in its infancy. Like a virus infecting theory, art and the academic world, cyberfeminism took on an international dimension, despite being heavily Western-centred, and also became an integral part of the work of Donna Haraway. An American philosopher and primatologist who has since the 1970s been battling against the hegemony of the male vision of nature and science. Now, let’s get back to Chloé Desmoineaux.

Before my feminist awakening, I wasn’t aware of the scale of the sexist clichés on my game screen.

As a teenager, Chloé spent hours on quite mainstream video games such as Duke Nukem. A series of shooting games played ‘in the first person’ (Editor’s note: when the player sees the action through the eyes of the protagonist). Duke Nukem, the main character, is a muscular figure known for his arrogant attitude, his sarcastic humour, his passion for firearms and his liking for women. The game has sparked numerous debates on the representation of genders and stereotypes in the video game industry. Because it is hardly worth underlining that he ticks all of the cliché boxes related to masculinity.

‘Before my feminist awakening, I wasn’t aware of the scale of the sexist clichés on my game screen,’ Chloé Desmoineaux explains. ‘I worked my controller to play video games created by an industry where the abuses of minoritised people are legion. On that subject, I remember a discussion with someone I met during a round table, the only woman working in a video game production company. Her male colleagues spent hours modelling characters’ breasts and making more than misogynistic comments about the protagonists they imagined.’

As is also the case in cinema, the male gaze (a visual and narrative perspective in the media constructed on the basis of the heterosexual male point of view) is a core issue in the video game environment. Without generalising, the feminist gamer remains outraged by the vast amounts of money being invested in big blockbusters. Formulaic packages intended specifically for male players. ‘The industry claims that it is ready to address the issue, but when you see the games which continue to be released today, you would have to say that any rethinking of gender and minorities remains superficial.’

What are we playing at?

Without having taken a dedicated video game training course, but by dint of changing her outlook on these issues, Chloé is progressively gearing her video game consumption towards alternative and independent productions. She is simultaneously discovering all of the narrative and political potential of certain game scenarios. In particular those conceived by Pippin Barr, a video game designer and associate professor in the Department of Design and Computation Arts, at Concordia University, Canada, or the creations developed by the Italian company, Molleindustria, which offers polemical, critical, even waspish video games, often under Creative Commons licence. ‘Talking about their releases, Every day the same dream is worth mentioning. A video game which explores our alienation at work, social conformity, the loss of meaning and the search for freedom.’

The game takes place in an entirely black and white world. In it we follow a besuited business man in his monotonous routine. The aim? Finding the means of shattering this daily grind. A minimalist gameplay which encourages the player to challenge the pre-established interactions. ‘It’s the side of video games which in the end people are pretty much unaware of. Because outside of the shooting games, the video game can also be a tremendous medium to criticise the abuses of the modern world and capitalism. It can narrate philosophical issues or artistic theories.’

Technofeminist, from lipstick to FluidSpace

When we ask her to pick out one of her projects, be it a repurposing of a video game or a participatory installation, Chloé quickly opts for Lipstrike. Literally, hitting with your lips. The contraction between lipstick and Counter-Strike (another first-person shooting game). Calling out the sexism in the video game world, Chloé imagined Lipstrike in 2017, in resonance with the #GamerGate polemic. This campaign of sexist harassment against women journalists and female video game developers. ‘I thought of this project as a live performance to be streamed on the Twitch platform. A female performer uses a lipstick connected to the computer, just like a controller, and plays Counter-Strike. The contact between the lips and the lipstick is equivalent to squeezing the trigger. This repurposing project defines me a lot because I have succeeded in linking my feminist commitment to an alternative controller. It was very well received in the alternative sphere I operate in, but I also had to deal with ultra-misogynistic, transphobic and disproportionately aggressive comments. You know that when you tackle these themes, you are potentially exposing yourself to hater reactions, often on the part of a community of far right gamers, as was the case at the time of GamerGate.’

Chloé also puts her feminist commitment into practice in several game art courses she gives at a private art school, and by means of FluidSpace. The hacklab she founded in 2021 in her workshop, nestled in the Belle de Mai district of Marseille. ‘It’s a space for visibility, thinking things through, meeting, gaming, experimentation and hacking. We hold weekly meetings, with the diversity desired, open to women and gender dissidents, to discuss our relationship with technologies, to game, open items, repair them, construct others, hack systems, invent stories.’

In this hackspace Chloé and other volunteers regularly hold workshops on discovering independent and queer games, the designing of alternative gamepads or interactive animations in 3D. And the video game activist will try to highlight this aspect of her work when she makes a brief visit to Namur. Chloé Desmoineaux is in fact one of the guest artists at the Under Construction exhibition taking place at the KIKK Pavilion, in the region’s capital. She will be there from July 24 to 30. An opportunity she has every intention of seizing in order to develop the way people perceive the video gaming world.

This content is brought to you as part of Propulsion by KIKK, a digital awareness project for and by women

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

The Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles: a billion blue blistering harmonies