Boris Eldagsen, a disruptive promptographer

Article author :

Formerly, he presented himself as a photographer artist. Today, the Berliner first and foremost calls himself a ‘promptographer.’ From his recent turning down of a prestigious photography award to his exploration of human consciousness, and taking in the shift in his creative process towards artificial intelligence (AI), a meeting with an artist producing works in a new genre.

‘AI images and photography should not compete with each other in an award like this. That is why I will not accept this prize. I entered to find out if competitions were ready to respond to AI images, and the proof is that no, they are not,’ wrote Boris Eldagsen on his Instagram account in mid-April. As we discussed on kingkong in one of our most recent articles, a prize-winner at the recent Sony World Photography Awards, the German artist turned down his award, disclosing that his image had been created by AI. A disruptive step taken in order to give rise to an essential conversation for both the art itself and for our democracies.

‘Since my turning it down, the competition has removed me from its website and from the exhibition dedicated to the prize winners, without any comment,’ regrets Boris Eldagsen. ‘Nobody within the organisation reached out to have a discussion with me at the prize-giving ceremony, to which I had travelled. I even took to the microphone to explain my approach. What are they going to do next year, when they receive a stack of entries with images sourced in AI, in all the categories available?’ There would nevertheless be so many means of addressing the subject: establishing a clear position, be it for or against AI within a photography competition, opening a special category for creative works with origins in these technologies, inviting the major decision-makers of the photography milieu to sit round a table together and get the debate started, etc. ‘Denying the problem is quite simply burying your head in the sand without admitting that the world of photography is not ready to respond to the Big Bang which AI represents,’ he continues.

Although the picture he presented at the competition – ‘The Electrician,’ one from a series entitled ‘Pseudomania’ – seems photorealistic, the black-and-white portrait of these two women presented in the style of the beginning of the 20th century contains several flaws typical of AI: the pupils of one of the women are looking in different directions, some nails seem to be absent from various fingertips, and the dress of the other figure merges into the skin of her arm. Boris Eldagsen concedes that his picture could have been identified as having been created by means of an AI, but when he learned of his victory, he did not appear surprised either.

Very critical of the competition’s radio silence policy, for his part the artist declares himself pro-AI. But he above all wishes to refrain from a dangerous conflation: ‘Photography and AI are two very different universes. A short time ago Christian Vinces, a Peruvian photographer colleague, suggested the term ‘promptographer,’ which I find very eloquent, as it refers to the mode of production of these photographs.’ By this is meant an artist who uses prompting technology and AI to create images. The term has not (yet) been logged on Larousse, but it suggests a considerable debate is in the offing as regards the addition of AI to the professions related to all that is visual. It may well turn out, in fact, that opting for a more transparent terminology is an avenue worth encouraging to exploit the creative possibilities of AI.

Well before employing AI in his photographic process, Boris Eldagsen’s pictorial relationship had first of all commenced with the painting and drawing to which he devoted himself during his path through art school. Somewhat by chance, such as an unexpected art form, he decided finally to explore photography. From black-and-white to colour, from the street photography he began with in India, to a much more eclectic documentary style he has now been involved with for some thirty years, themes which embrace consciousness and the human condition are the focus of his photographic work, influenced by the Symbolists, the surrealists, needless to say, but also by Jérôme Bosch and Rembrandt, especially the latter’s treatment of light. The photographer had moreover initially studied philosophy. ‘I have always wanted to find answers to the major questions of life. I believe in a collective unconscious, in archetypes. I think it is that which brings us closer together and that art can act as a medium in this process, which is hard as a creator because the contemporary art scene is more interested in making political comments on the global situation. I am not saying that this art is not necessary, but I wish to address a deeper question on what leads us to unleash such disasters, be they environmental or political.’

Also a member of DAF, the Deutsche Fotografische Akademie, and a guest lecturer at some of the most prestigious photography universities and schools the world over, such as the Victorian College of the Arts in Melbourne, it was only very recently that Boris took up experimenting with AI. A means, for him, of extending the boundaries. ‘In terms of photography, I had reached an endpoint regarding what I had wanted to produce. Taking it a step further would have required having access to larger budgets, but I have always worked with few resources. It is that which forges our creativity, in no matter what art form, moreover.’ From 2015 onwards, the notion of AI applied to photography began to be gradually more widely discussed. In 2108, the platform This Person Does Not Exist emerged and allowed a random human face to be generated with a single click. Around the summer of 2022, DALL∙E1, and subsequently its improved version DALL∙E2, catapulted by the American giant OpenAI, vastly opened up the realms of possibility. Even if large numbers of other AI platforms already enabled experimentations with the creation of images. ‘My first photo by using AI, was with Disco Diffusion. It took me 20 minutes. A French photographer friend later told me about the waiting list to test DALL∙E2. Once I had access to it, before he did, for that matter, I started carrying out tests. It was at that time, around last August, that I realised that it was the creative tool I had always been waiting for.’

Since he launched his first online workshop dedicated to AI and to prompting last January, Boris Eldagsen has been receiving requests from far and wide to provide training courses on the subject. Professional photographers, photojournalists, photography teachers, editors of specialist magazines, but also designers, painters, jewellers, etc. The growing interest concerning AIs extends beyond the single world of photography. Today, Boris has abandoned the various jobs he had in digital marketing to make ends meet in order to focus entirely on AI. And he has also unwittingly become an activist in a mere few weeks. ‘Since the episode of the Sony prize, the subject had been on the lips of everybody who is somehow connected with the photography milieu. In Germany, in any event. But AI applied to the image also raises democratic issues. The media need to be trained in the ins-and-outs of these technologies so as to be able to recognise deepfakes on the web. But in order to carry out fact-checking, you need to have the means to do so, the human resources, the time required, which not all editorial boards have available. Incidentally, out of all the interviews I granted, only one international media outlet asked me how to verify that the photo in which I am standing next to The Electrician is indeed real. I had to prove that the picture was taken at an exhibition opening event in Berlin, that they could anyway go there to see the installation.’

It is in learning to master these tools that we remain creators of our images.

The as-of-now promptographer does not have any particular technique and operates through trial and error to deepen his prompting knowledge. To get started, Boris Eldagsen for that matter recommends learning by getting to grips with it, asking complex prompts, which seem improbable, or even impossible. ‘See what the machine suggests to you, respond to it, dialogue with it. Sometimes, a misprint in a prompt can also bring about nice surprises. Be the Christopher Columbus of AI.’

DALL·E, Stable Diffusion, Adobe Firefly and Midjourney; these AIs and their options are improving day-to-day, although they all use the same mechanism: they interpret and generate images on the basis of a written command, the much-vaunted prompt. You can use up to 11 prompt elements and fine-tune your requests as you get nearer to the wished-for result. So, is it a photographic art or not? It is here that the human-machine relationship comes into play. A power relationship, or one based on collaboration? ‘If I only use 2 prompts out of the 11 possible, it is the machine which decides the other 9. It is in learning to master these tools that we remain creators of our images. I can decide the scenography, the type of light, the elements which constitute my composition, but that requires knowing what to say to the AI. In this way, the AIs will remain a tool at the service of the art, just like the camera.’

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

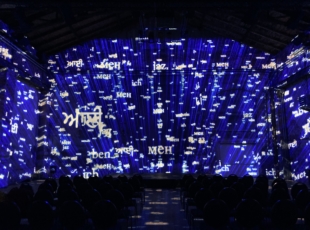

The Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles: a billion blue blistering harmonies