Bringing art conservation-restoration out of the shadows

Article author :

Unknown to the wider public, operating where the sciences and the history of art intersect, always at the vanguard of the museum sector calendar, the discipline leans on a wide palette of technologies, far removed from the idealised image of restoration by means of a fine paintbrush. And, as is true for numerous professions, the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) is both troubling and fascinating.

Tucked away within the very heart of Ixelles is a shared art conservation-restoration workshop. At the present time, two of the three individual workshops are occupied by two restorers. One specialised in ethnographic art and archaeology, the other in painting. More specifically, in modern and contemporary art, although Marine Dandoy also restores old paintings. ‘Restorers working collectively is quite commonplace. I know very few colleagues who work on their own; it’s a solitary profession to start with. Plus, when you work with several people, you can pool your expertise, ask other people for their opinion on an ongoing restoration, have someone else give a different perspective on your work.’

My first client was Beaubourg.

Marine dandoy

A graduate of La Cambre in Brussels, one of three art schools in Belgium to offer training in the ins-and-outs of the profession, along with the Antwerp Académie des Beaux-Arts and Saint-Luc in Liège, Marine Dandoy left for Paris in 2020, at the end of the first lock-down. She had landed a three-month training programme there at one of most prestigious cultural institutions the City of Light has to offer. ‘When this programme finished, I was able to continue my collaboration as a conservator-restorer at the Pompidou Centre. It’s a bit mad, really, but my first client was Beaubourg.’

Several times a year, Marine makes the return journey between her Ixelles workshop and Paris, often when this pillar of modern art needs to bring in reinforcements to its regular team of conservators-restorers, as larger exhibitions are being prepared. ‘The profession can thus also get you to travel about a bit,’ she adds. Hidden aspects, but also simplistic leaps of assumption: the profession contains and has to face large numbers of both. Over the course of our conversation, the Brussels restorer endeavours to deconstruct them: ‘You have to bear in mind that there are actually other specialisations than just painting in restoration: ceramics, photography, textiles, etc. It is wrongly thought that every restorer is de facto a good drawer. I am very often asked if I can paint, but never if I am good at chemistry or at physics. However, in this profession, you have to know how each material which features in the design of a work will react to the conservation and restoration processes we intend to use. The frames may be manufactured from wood, canvas, metal, paper. Each type of paint, oil, watercolour, gouache, or even a mixture of these techniques, has its own specific chemical properties. For the competitive entrance examination for La Cambre, I remember the number of questions on this subject. Somewhat naively, I thought I would emerge from it with a more than sound knowledge of the history of art and pictorial techniques.’

One comes across paintbrushes infrequently in her workshop. Amongst her tools one finds scalpels, magnifying glasses, cotton wool, varnish, brushes, spatulas, measuring flasks, etc. You would think you were in the den of a laboratory assistant. And therein lies another considerable anomaly which ignorance of the profession gives rise to: the relationship to the status of the artist. ‘Our mission is in a way to be invisible. We thus position ourselves below the artist whilst simultaneously giving their work a new lease of life. But without the restorers, it would be difficult to still be able to view works in museum galleries.’

But side by side with that of its progenitor, when have you ever seen mentioned the name of the most recent person to have restored the work of art your eyes have come to rest on in a museum? Even though the profession has been rendered invisible, all artworks are continually restored. It is not necessary to wait for a chip in a ceramic object or for a tear in a canvas before these specialists get down to work. It is in this way that the conservators of artworks are the custodians of cultural heritage, who attempt to preserve the aesthetic and historical integrity of each piece which is entrusted to them.

From artists’ paintings found within private collections to the greatest masterpieces, Marine Dandoy approaches each work with the same level of interest. Although some are more noteworthy than others. ‘When I was working on Pablo Picasso’s Le Printemps, I was really honoured to be able to add my own contribution. It is worth noting that each restoration has heritage interest. Our goal is also to further knowledge about the artist, their style, their techniques, the material history of the work, or actually about the restoration methods themselves.’

It is impossible to embark on the restoration of a painting without knowing what will be found layer after layer. ‘Often clients ask us if we couldn’t simply repaint a small visible stain,’ smiles the restorer, ‘but we cannot work merely on the surface.’ It is then necessary to reach out to historians and external specialists to have the artwork analysed, or even to decode any previous restoration work it may have undergone. Infrared or ultraviolet photographs also enable an understanding of what is going on underneath. ‘Unlike the workshops of major museum institutions such as the Pompidou, I obviously do not have access to these technologies – which are space and cost intensive – in my workshop.’

During their studies, in order to familiarise themselves with these cutting-edge technologies, budding Belgian conservators-restorers regularly beat a path to the Institut royal du Patrimoine artistique (IRPA), in Brussels. A key hub of art conservation-restoration, which also endeavours to render the profession more visible, as more and more museums are increasingly doing. The National Gallery in London, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York offer their visitors the opportunity to go and meet conservators whilst they are working in their workshops. The Louvre Lens has for its part taken a different direction. Since its creation in 2012, its restoration workshop and its vast reserves are permanently visible. A way, perhaps, of stirring the curiosity of young people still wondering about which direction to take in their work lives.

Algorithms at work

The profession is evolving as rapidly as the technologies it uses, but of late AI is throwing down challenges because it may trigger upheavals in the trade. In 2022, the British start-up, Oxia Palus, which endeavours to recreate lost masterpieces by using AI, allowed visitors to the Paris Focus Art Fair to discover a previously unseen canvas painted by Vincent Van Gogh. Entitled ‘Two Wrestlers,’ in it are represented two men with nude torsos engaged in a wrestling match. The Dutch painter is thought to have produced the work around 1886 – he mentions it in a letter addressed to his brother – but it was subsequently painted over with a floral still-life currently held at the Kröller-Müller museum, in the Netherlands.

A process which has led several to raise questions regarding the intrusion of these algorithms in art, even though they could just as well be considered assistants useful to restorers. So far, Marine does not envisage AI being able to imperil her profession and is instead trying to explore its possibilities. ‘AI could accelerate historical research into the art we are restoring, an essential stage of the work process but one which is pretty time-consuming. It could also assist us in the cleaning process to understand the limits of the work. With projection images, we could also employ AI to reconstruct a missing section, for example.’ This has already been carried out at the Rijksmuseum in 2021, when an AI aided the restoration of Rembrandt’s ‘The Night Watch.’ A vast canvas from which entire sections had been cut in order to facilitate its transfer. So, taking the place of the profession, then? The restorer does not believe it to be the case. The profession demands a measure of sensibility and inventiveness which no technology could hope to equal.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

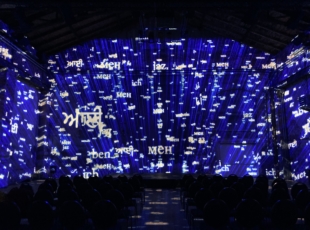

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

The Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles: a billion blue blistering harmonies