The forgotten figures of computer science #1: Annie Easley

Article author :

The American Annie Easley (1933-2011) is the first of three women kingkong is presenting a portrait of as a means of talking about the forgotten figures of the history of computer science. Aline Pesesse, who has written a dissertation in the field of the labour sciences, introduces her and talks to us about the invisibilisation of women in the sector.

Aline: you were researching a dissertation in the field of the labour sciences when you became interested in the forgotten figures in the history of computer science, and especially in Annie Easley, born in 1933, an Afro-American engineer and mathematician who happened to find her way into computer science a little by accident…

Aline Pesesse: That’s right. Originally from Birmingham (Alabama), she began studying pharmacy in the 1950s before abandoning her education to get married and move to Cleveland. There were no schools teaching pharmacy in the area. She therefore decided to look for work and landed a job at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NACA, an agency which became NASA in 1958.

She was employed as a ‘human computer.’ What does that mean?

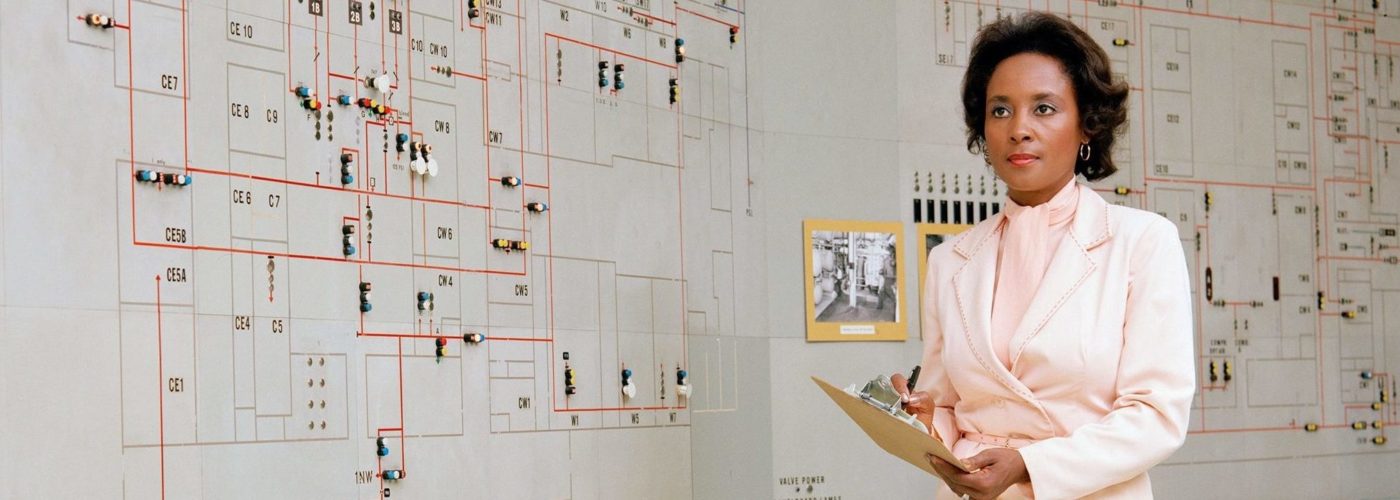

She was doing what a computer does today: analysing problems and solving them by working out calculations by hand. She in particular got involved in running simulations for a new reactor, the Plum Brook Reactor, today called the Neil Armstrong Test Facility. This Plum Brook complex hosted ground tests carried out for the international space community.

Machines would eventually replace human computers such as Annie Easley. She had the cleverness then to evolve with the technology by becoming a computer programmer. She contributed to the development of code which in particular served the evolution of battery technology, a technology used to design the first hybrid vehicles. Which is to say that the results of her work are still being applied today.

You explain that when she started to work for NASA there were only three other Afro-American employees….

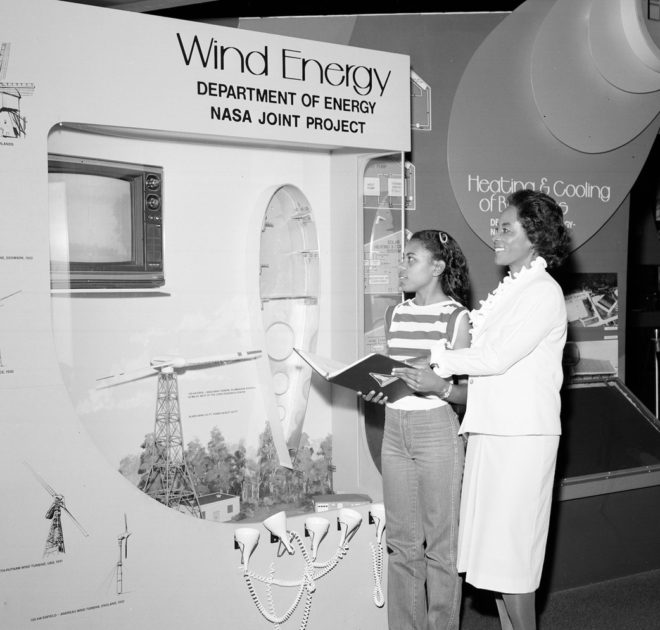

Yes, it is for that reason that, alongside her work, she became involved in advocating students from minority backgrounds to consider careers in STEM (acronym for science, technology, engineering and mathematics). She also took on the role of equal opportunities counsellor at NASA. This role consisted of cooperating with supervisors in the overseeing of complaints concerning sexual, racial and age discrimination. She in particular succeeded in having an agreement concluded allowing women to wear pantsuits. All that would remain under the radar of history. For that matter, in her essay on The Forgotten Names of the Digital Industry, the author Isabelle Collet primarily refers to Mary Shelley, Ada Lovelace, Hedy Lamarr, Grace Hopper, the women programmers working on the ENIAC, and human computers, but I have struggled to unearth information about Annie Easley. As a black woman, she has undeniably been subjected to an additional layer of invisibilisation, the outcome being that very little is known about her.

On hearing all of that, we can’t help thinking of the film ‘Hidden Figures’ …

What this film shows very well, is that Afro-Americans were tolerated at NASA, but that they remained segregated, with the cafeteria and the toilets ‘for coloured people.’ The film’s three heroines are three other forgotten figures in the history of technologies: Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson and Dorothy Vaughan.

How did you even discover these women?

I wanted to work on the glass walls which make certain professions inaccessible for women. But what I discovered is that women had a presence at the very beginnings of computer science, but it’s just that over the decades they disappear! If I ask a person in the street, ‘Name me a female pioneer in computer science,’ nobody will be able to give me any names.

What has made it so that, historically, women like Annie Easley have disappeared from the computer science professions?

In the middle of the twentieth century, computer science and programming didn’t exist as such. As I explained with the example of Annie Easley, we need rather to talk of human calculating ‘machines.’ It’s a painstaking job, one carried out by subordinates, which is therefore not of much value and it is that which made it accessible for women and why it was allocated to them: it was regarded as a continuation of secretarial work, which was almost exclusively female at the time. It was only later that programming became the economic concern we know today, and it was from that moment that it was considered too complicated for women to carry out and that men became increasingly involved in it.

And your dissertation talks especially about initiatives being implemented today to encourage women to reconquer computer science. What are they?

I focused on both public policies and on voluntary work. I talk in particular about Interface 3 in Namur and Brussels. These non-profit organisations have been running respectively for 19 and 35 years and have always been women-only. They raise awareness of and induct people into STEM by having them discover the professions and arranging training courses leading to qualifications. There are different targets: young women and adult women looking to return to work, in other words women who are unemployed or who have no academic credentials. And this last category is important because it runs counter to another cliché about these professions: you have to be ultra-qualified in sciences to work in them.

What strikes you in particular from the interviews with contemporary women computer scientists?

The importance of demystifying these professions and presenting them less as technical professions but more as professions based on relationships. In fact, the majority of the women professionals I met, be it in the public sector, banking, non-profit or transport, have a similar way of considering their work: a profession which serves to help people by finding solutions to their problems. All too often, information technology professions remain abstract even though, behind the tools, there are the people who will create them and, on the other hand, the people who will use them. It’s very concrete, it improves people’s lives and, for these professionals, the prevailing idea is one of being dedicated to users.

That takes us back a little to this notion of care which describes the care-providing professions as being the preserve of women…

Yes, we have to be careful not to essentialise them. But I think that if we want to diversify the profiles in these professions, they need to be presented differently. For that matter, in another way, the professions usually described as pertaining to care should also be presented differently. Geneviève Fraisse explained that being a nurse means holding someone’s hand, but it also means managing dirtiness, working staggered shifts, carrying heavy loads, and that, anyway, people see what they want to see in a profession. We need to emphasise the skills linked to a profession rather than merely naming them. And so we should say that computer science means listening attentively to people, it means providing help and it means finding solutions to human problems.

This content is brought to you as part of Propulsion by KIKK, a digital awareness project for and by women.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.