The forgotten figures of computer science #3: Ada Lovelace

Article author :

The English Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) was a pioneer of computer science. She was the first person ever in History to carry out programming. It is the mathematician and Emeritus professor from the University of Quebec, Louise Lafortune, who talks to us about her, and who revisits her own journey of over forty years in the service of the visibilisation of women scientists.

Louise Lafortune, thank you for granting us this interview. Could you explain to us who Ada Lovelace was?

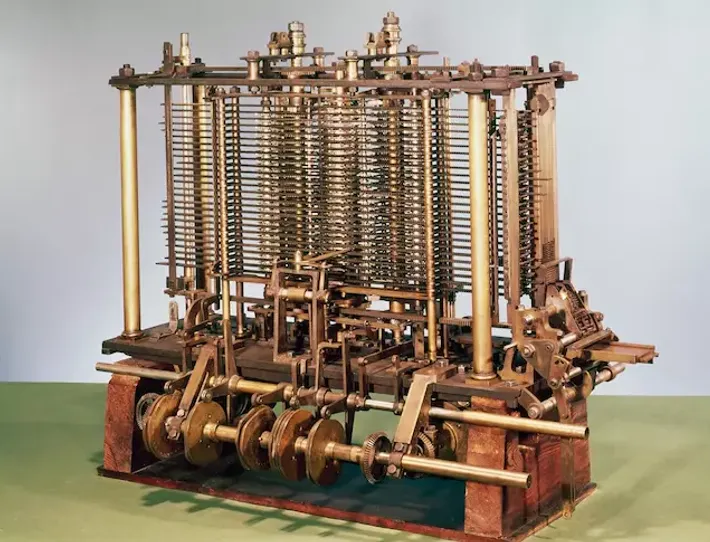

Her full name was Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, born Ada Byron. She lived in the nineteenth century, in England. She is often presented as the first programmer in History. She developed the first genuine computer programme by working on the analytical machine, a precursor of the computer. Within the female figures in sciences, she could be considered one of the lucky ones, one of the few whom we talk about increasingly regularly. There is even an Ada Lovelace Day!

The Ada Lovelace Day. What is it about exactly? And why is she better known than the majority of the women mathematicians whom your research has focused on?

It is a day which is held on the second Tuesday of October. It is celebrated principally in the Anglo-Saxon world and its goal is to showcase women who are active in the sciences. I think that this day was given the name Ada Lovelace because, unlike women mathematicians, she is more directly associated with the discipline of computer science. One can establish a direct link between her and the new technologies, which bestows an aura on her.

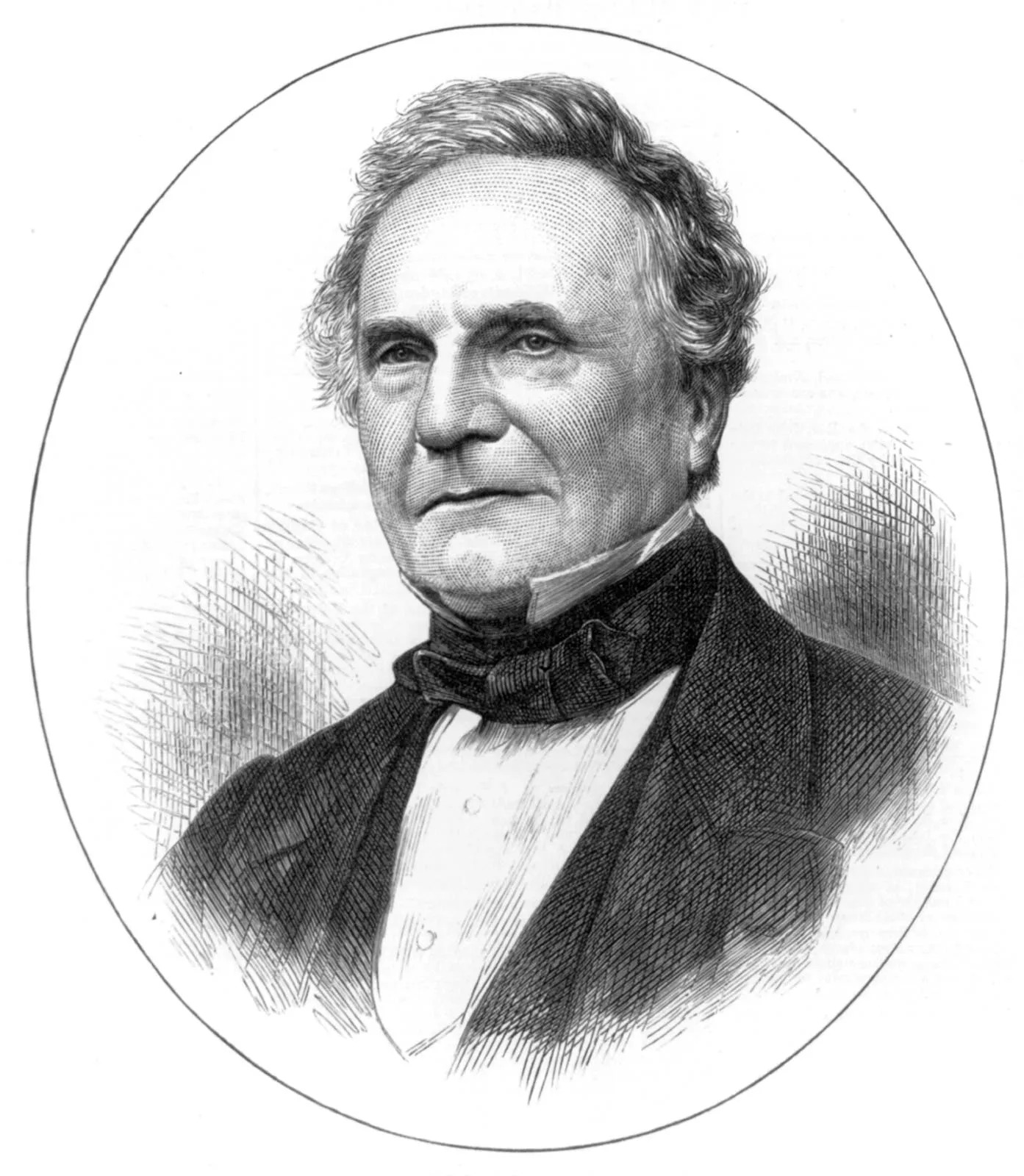

You also say that perhaps it is because she worked with a man, Charles Babbage…

Yes. For that matter, it is difficult, as far as those two are concerned, to establish who influenced whom. Charles Babbage created the machine on which Ada Lovelace would programme. The two had a relationship based on mutual admiration. But it is similar to the influence Mileva Einstein had on Albert Einstein; there is a tendency to minimise it.

How did you yourself, in the 1980s, begin to take an interest in Ada Lovelace?

I was doing a Master’s, the subject of which was the history of women mathematicians. I was studying their personal life stories with the idea of developing a teaching application out of it. Because, in parallel with my doctorate, I had begun a course on ‘Women’s Studies’ – it doesn’t go by that name nowadays – but it was the name of a programme at the Institut Simone de Beauvoir de l’Université Concordia, here in Montreal. In it we studied famous women, but very few from the scientific domain. I wanted to look deeper into this aspect.

You thereby became a pioneer on the place of women in the STEM (for Sciences, Technologies, Engineering and Mathematics), in particular by devoting several works to the question, by contributing to a manifesto and by creating an international movement (the International Organisation of Women and Mathematics Education, the IOWME). Is this question still relevant?

Of course! Because in some respects we have even regressed! In twenty years, the position of women in engineering is instead ebbing or stable, but it isn’t increasing, despite the Canadian 30×30 objective, which aims to have 30% of engineers being women by 2030. As minimal as it is, it seems difficult to achieve this objective. At the moment I am working on a study in which we are focusing on women engineers in the areas where they represent less than 20% or even less than 15% of the workforce, in other words the mining, chemical and oil industries. We are asking the question: why are they not getting into these areas? What can be done so that they start going there? The data gathering is underway, but what I can already say is that when the prospective female student says ‘I am going into mining engineering,’ the opinions elicited differ from when the young girl says ‘I am going into medicine.’ It is that stereotype that I wish to change.

You talk about the ‘danger of the stereotype’ by explaining that teachers, parents and other entourages, through their actions and words, have a significant influence on the study and career choices made by girls. How can we develop beyond that?

First of all, by progressing away from THE and instead using SOME. In the sense that we stop saying ‘the girls are this’ or ‘the boys are this,’ because neither girls or boys form a homogenous group. In the construction of one’s own identity, it is very important to be able to distance oneself from these stereotyped groups. There are, in addition to the questions of language, those which I call reflective interactive practices. That applies to schools, but we could extend it to parents, the media, to company boards of directors, etc. It’s a question of considering your own actions, your own practices and words: are they perpetuating stereotypes? And I recommend that this is carried out through interaction, by which I mean in groups, because it is easier to detect the words which perpetuate prejudices and then take steps and implement changes.

In these reflections intended to take place within your organisation or even within your own family, you pay particular attention to language. Could you tell us more about this?

There are currently flourishing numerous reflections on inclusive writing or, more widely, inclusive language. This can take different forms. Personally, I am sympathetic to the decisions taken by the Office Québécois de la langue française, which is contributing to feminising language. But beyond this feminisation, let us look to see if our own writings are not perpetuating other stereotypes. Racist, for example. Or social class. From my own written vocabulary (it is sometimes more difficult regarding oral expression) I have banned the phrases ‘we have to’ or ‘we must,’ or the imperative mood. Why? Because if I say these words, I position myself as an expert, as if I held the truth and I had ascendancy over the people I am addressing. The shift from ‘the’ to ‘some’ is part of this reflective process: let us think of the people who are reading us and about how they feel when they are reading us. Today, I believe that in our schools (when discussing French grammar) we no longer say ‘the masculine form takes precedence over the feminine.’ At least I hope so! We had no idea of the violence and the impact of such a phrase. Another example: today, in my field, we talk about ‘nursing sciences’ or ‘nursing techniques.’ That avoids saying ‘nursing care,’ which is vaguer. And that gives real value to the work of nurses by recognising it as a science in its own right.

There was the attack in Quebec which drew worldwide attention and which targeted female engineering students. But there is also, on a daily basis, for women, what you call ‘micro-aggressions,’ which you yourself have experienced in your career…

We will never be able to quantify the impact of an event such as this mass killing. But, at my own level, yes, I have been faced with colleagues who suggested secretarial work to me, even though we had equivalent qualifications. And it was by removing all references to my feminist commitments from my CV that I was able to land the job I coveted. Today, I condemn the weight we place on girls’ shoulders. We tell them that they are capable of doing sciences, that they can go there, but we rarely ask others to change their attitudes and to think about their own words when the girls actually do go there.

This content is brought to you as part of Propulsion by KIKK, a digital awareness project for and by women.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.