AI is being invited to the Paris Olympic Games, raising a lot of questions

Article author :

It’s a first in Europe. To ensure the safety of the summer Olympic Games taking place in Paris from July onwards, the French government has enacted a law which authorises the use of a video surveillance system assisted by artificial intelligence. A decision which many in France find troubling, but which is also giving rise to misgivings here in Belgium.

The ‘Loi JO (Jeux Olympiques)’, to give it its name, was passed by means of a fast-track procedure in March of last year. Its aim: to define the set of means and actions legally permitted by the government and the city of Paris to ensure the security of each person during this global event taking place in the French capital in July and August later this year.

Amongst the battery of measures and rulings contained within the law, Article 7 provides the authorities with the possibility of putting in place a system of video surveillance cameras to scrutinise the deeds and movements of the millions of people who will be strolling around Paris for the whole Olympic Games period. But we should be mindful that there is something quite distinctive about this measure, as it will be ‘supported’ by artificial intelligence.

The VSA in practice

Named ‘VSA’ (for ‘vidéosurveillance algorithmique’, or algorithmic video surveillance), the system chosen in France uses, as its name indicates, a network of algorithms to process and review the millions of images which will be taken by video surveillance cameras. This specially trained artificial intelligence will be capable of detecting abnormal events in a series of predefined situations. These situations have been specified in the French government’s ‘Loi JO’. In it are found anomalous behaviours such as one or several persons or vehicles not respecting the direction of traffic, crossing into forbidden areas, an abnormal surge in the crowd, one or several people lying on the ground, too large a density of people in a given location, but also events which are out of the ordinary such as outbreaks of fire or the detection of unattended packages.

The technology, developed by the Paris-based Wintics company, has already been tested, less than a month ago, for the Depeche Mode concert held at the Accor Arena in Bercy. Six cameras were deployed by way of a trial. The artificial intelligence managing them had been instructed to send a message in the event of the detection of something abnormal in comparison with its nominal observational frame of reference, without, however, leading to any people being detained.

Is a Pandora’s box being opened?

Be that as it may, this new measure is provoking a lot of reactions. For the advocates of this technology, it provides effective assistance for surveillance; for its detractors, it is a software programme which risks a reduction in liberties. ‘There is no behavioural analysis, no facial recognition, no reading of number plates’, Matthias Houllier, the co-founder of Wintics, the company selected following the publishing of calls for tender to provide security for the Olympic Games, explained to the RTBF broadcaster.

But there is far from being a consensus of opinion as to the use of artificial intelligence as a support for surveillance. Several French lawyers and representatives of the National Council of Bars (CNB) are not reassured: ‘from the lawyers’ perspective, this technology is raising more fears than hopes. We understand that there need to be measures to ensure the safety and the smooth running of a sporting event like the Olympic and Paralympic Games. For all that, a fair balance needs to be found between the need for security and respecting individual rights and liberties,’ they explain, once again on the RTBF.

Numerous associations, including Amnesty International, are concerned about the possible impact on individual liberties that these measures may have. In its press release, the human rights group substantiates its fears: ‘the fact that algorithms analyse the behaviours of individuals live rests on a gathering of personal data to a worrying degree as regards the right to privacy. Any surveillance of public spaces is an interference of the right to privacy. To be legal, such interference must be necessary and proportionate.’

And that is not all, as the NGO also highlights the risks of stigmatisation linked to the training received by the AI responsible for analysing the camera images. ‘Calling it algorithmic video surveillance still implies the use of algorithms. In order for the cameras to detect “abnormal” or “suspect” situations, algorithms need to be trained. By human beings. It is people who will choose which data will train the algorithms by determining beforehand what is “normal” or “abnormal”. This so-called “training” data may include discriminatory biases. Might a homeless person or somebody playing music in the street one day be considered “suspect” because their behaviour does not correspond to the established “norm”? This is the type of risk run by algorithmic video surveillance.’

Belgium also has misgivings

In Belgium as well, many are taking a dim view of this first use of artificial intelligence within the context of safeguarding public spaces. And for good reason, as this technology very strongly resembles another very specific means of surveillance: face recognition. And the specialists for that matter confirm that this technology is good-to-go, and absolutely deployable within the system which will be implemented for the Olympic Games. Only the wish of the company responsible to restrain this functionality within the programme is preventing its use.

Reasons to be concerned, therefore, including here in Belgium. Because there are cases of events being used to set up systems of a similar type. This was true in Russia, where video surveillance assisted by artificial intelligence was inaugurated for the 2018 World Cup. And whilst at the time the Russian government announced that it was a temporary measure, the system has never been dismantled since and is widely used by the authorities to consolidate their power, including using the apparatus to track demonstrators or dissidents opposed to Vladimir Putin’s regime.

And the French government’s promise to only use the system for a maximum period of one year in no way reassures sceptics in France and elsewhere. To such an extent that, here in Belgium, several associations have filed a petition with the Brussels Parliament: called ‘Protect my face’, this petition requests the pure and simple banning of the use of artificial intelligence systems enabling face recognition in the capital’s public sphere.

A story, projects or an idea to share?

Suggest your content on kingkong.

also discover

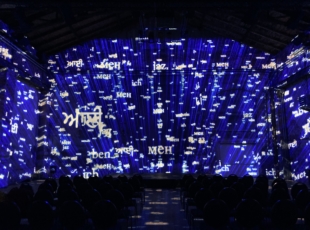

From Belgium to Japan, the new territories of creative digital creativity

Stereopsia, the key European immersive technologies hub

NUMIX LAB 2024: creating bonds and building the future of digital creativity